Nabendu Ghosh recaps in his autobiography, Eka Naukar Jatri/ Journey of a Lonesome Boat, vivid memories of the making of Do Bigha Zamin, which was to initiate a new chapter in Indian Cinema. Plus, a special feature by Ratnottama Sengupta

Balraj Sahni and Nirupa Roy in Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen

Asit Sen and I started preparing the shooting chart for Parineeta which was to be made under the banner of Ashok Kumar Productions. This is when Hrishikesh Mukherjee returned from Calcutta and right away he narrated a story to Bimal Da.

It was the story of a farmer, Shambhu Mahato. He lived with his wife Parvati, his 10-11-year-old son Kanhaiya, and his aged father. He lived in a village that was under a zamindar whom Shambhu had failed to pay his khajna/ lagaan for three successive years. Shambhu had a piece of land measuring two acres. The produce was barely enough for the subsistence of the entire family.

One day the zamindar summoned him and declared that, if the dues were not paid within 48 hours, he would drag Shambhu to court. The zamindar had an ulterior motive in thus closing in on Shambhu: he wanted to grab the two acres of land as it was just right for setting up an industrial unit. Once that came about, the zamindar would be many times richer.

At such short notice, Shambhu clearly could not come up with the claimed amount. The zamindar lodged a case and the judge granted the farmer three months to pay the tax.

Shambhu and Kanhaiya find shelter in a basti peopled by labourers

In an agricultural country like India, land was not just two acres of soil; it was a metaphor for a mother who feeds her children and nourishes their growth. So Shambhu leaves for the big city of Calcutta, where he would toil hard and earn enough to save his two acres. Intending to pitch in, young Kanhaiya joins his father on the trip. The two find shelter in a basti peopled by labourers and vendors of every description. Shambhu finds a job as a rickshaw puller while Kanhaiya is taken under the wings by a young shoeshine.

Two months go by when misfortune strikes. Shambhu is disabled by an accident. Back in the village, racked by misgivings as both, money orders and letters dry up, Parvati ventures out in search of her husband and lands in the city – only to be led astray by miscreants. When the family comes together and makes their way back to the village, three months have elapsed and the two acres are now home to a factory.

******

The roots of the story lie in Dui Bigha Jomi/ Two Acres of Land, a long poem by Rabindranath Tagore. It had been given a contemporary context in a rapidly industrialising India. Further inspiration came from the Italian film Bicycle Thieves. We – Bimal Da, Hrishikesh, Asit and I – had the opportunity to watch the film when the first International Film Festival of India was held in Bombay in February 1952.

“Balraj Sahni in Do Bigha Zamin” – a page from Nabendu Ghosh’s autobiography Eka Naukar Jatri

Who had drafted this story of Do Bigha Zamin? Salil Chowdhury – that young man from IPTA who wrote songs and poems, whose composition Kono ek gaanyer badhur katha encapsulating the horrors of the Bengal Famine of 1943, through the story of a village woman whose idyllic life full of dreams and harmony is ruined by the arrival of the manmade famine – “Churchill’s secret war’ that had robbed 5,000,000 Bengalis of home and life. The song written and composed by Salil Chowdhury had brought greater fame to the highly regarded singer Hemant Kumar when it was released in 1949.

We – every one of us led by Bimal Da – instantly liked the story. Bimal Da told Hrishi, “Ask Salil Babu to come to Bombay right away.”

Salil arrived in three days’ time. The moment he set eyes on me, he bent down to touch my feet and said, “Nabendu Da, I am here to join your team.”

I replied, “Our team gains by your presence. You are more capable than ‘Sabyasachi’ – Arjun could shoot arrows with both hands with equal dexterity and skill. You are four-armed – you can write songs, you set them to music, you write stories and poems too!”

Salil’s face lit up with a shy smile. But Asit, Hrishikesh, and the cameraperson laughed wholeheartedly, which brought Bimal Da to the office door. “What’s the cause of such merriment?” he asked.

“We are delighted to have Salil Babu in our team.”

******

Bimal Da got busy completing the screenplay of Do Bigha Zamin with Salil and Hrishikesh. On the other hand, the script of Parineeta too was complete – as was its casting. One morning Ashok Kumar told Bimal Da, “Since everything is ready, start shooting Parineeta at the earliest, Mr Roy.”

“Certainly, Mr Ganguly,” Bimal Da responded enthusiastically. And within a fortnight, Parineeta went on the floors at Bombay Talkies. And in Mohan Studio, Bimal Da started shooting DBZ under his own banner, Bimal Roy Productions. He had set up his 200-sq-ft office on the ground floor and above it he had a conference room. He was both the producer and the director, so his responsibility had gone up manifold. He had signed an agreement with a Gujarati financier who was keen to complete the film as fast as possible so that he could release it in the shortest period and profit from his investment. This compelled Bimal Da to shoot Parineeta during the day and Do Bigha Zamin at night.

The story of a rickshaw puller involved a number of outdoor scenes. And since the story was set in Calcutta Bimal Da travelled there to shoot the key scenes including the now classic race between the rickshaw pulled by a man and the horse-driven carriage, on the Red Road close to Victoria Memorial Hall.

The race on the Red Road close to Victoria Memorial Hall

******

Also shot on the streets of Calcutta were the shoeshine scenes involving Jagdeep and Master Ratan.

The casting of Jagdeep as Laloo Ustad speaks volumes about Bimal Da’s eye for characters. Prior to Do Bigha Zamin he had acted in Dhobi Doctor (1954) which I had scripted for Phani Majumder. He was in a tragic role there but here he was quite the opposite – an effervescent, chirpy soul. At the outset, Bimal Da asked him if he knew how children polish shoes. He gave him tips, he helped him learn the ropes of the job, how they draw the attention of their customers. He allowed the young artist to add his own flourishes – and Jagdeep became a star of sorts! Eventually, he grew up to be a full-fledged comedian.

Nirupa Roy convincingly transformed into a farmer’s wife

The casting of Nirupa Roy in the role of Parvati was even more outstanding. Because, prior to Do Bigha Zamin, she was seen as a leading lady but only as a goddess. But the ‘Queen of Mythologicals’ came from a village in Gujarat and could identify with the woes of a village woman whose husband and son are away in the city for livelihood. So she convincingly transformed into a farmer’s wife whose journey to the big city is beset with hardship.

Like Jagdeep, another minor artist gained eminence by selling the much-loved street food of puchka. Who was this actor? Mehmood, the elder son of the once famous Mumtaz Ali who was, at this point, going through a low tide in life.

******

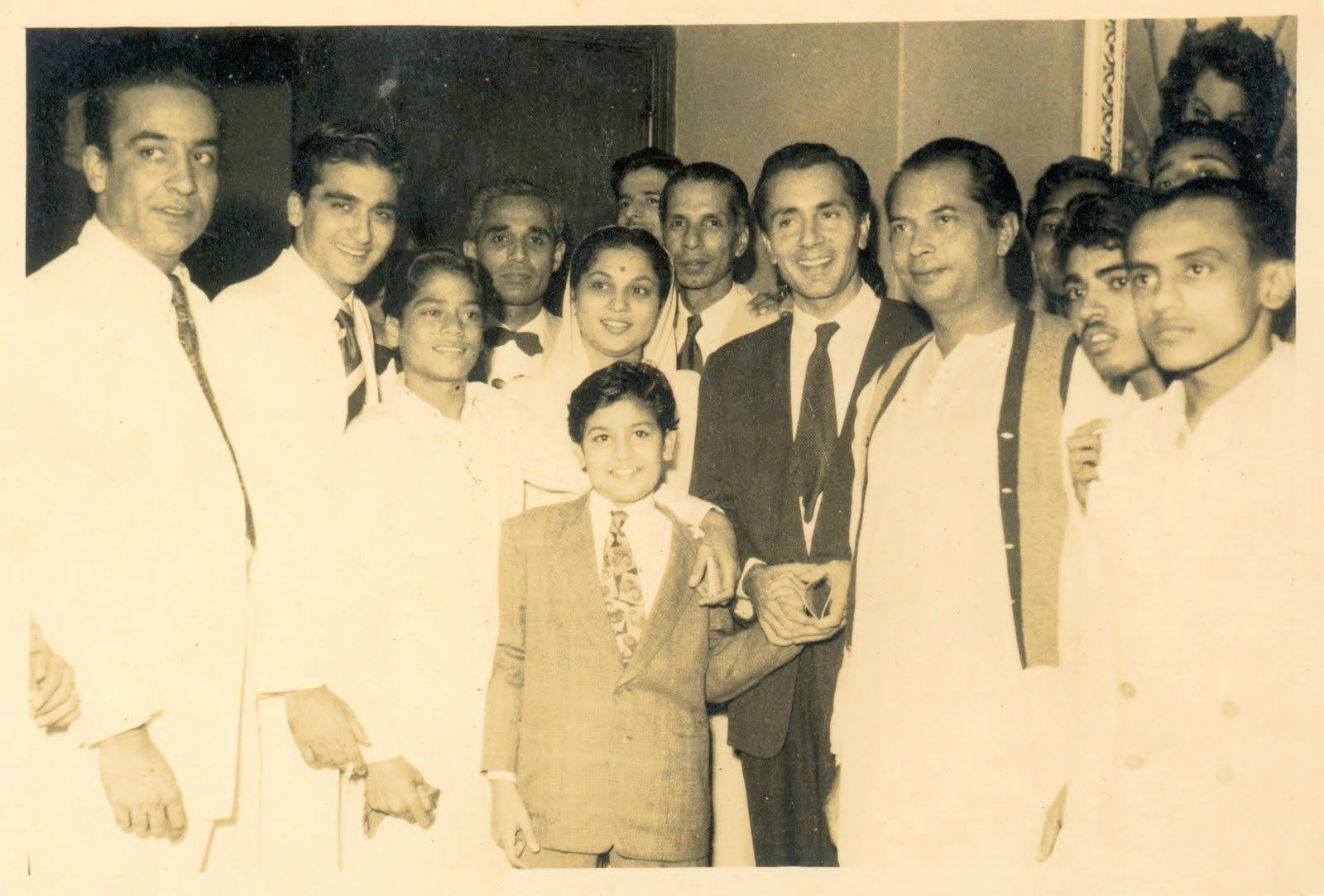

Bimal Roy, Jagdeep, Nirupa Roy, Balraj Sahni, Rattan Kumar and Sunil Dutt

A couple of months before this I was desperately looking for a house on rent so that I could bring over my family – wife Kanaklata and sons Dipankar and Subhankar – from Calcutta. Boudi – Bimal Da’s wife Manobina – had got the information about a house minutes away from Malad station in the East – the other direction from Bombay Talkies and Van Vihar, where we were camping. I went across with her and was enchanted. It was a Goan-style bungalow that stood next to a school by the name of Fatima Devi English School. There were a handful of such cottages in the neighbourhood, Pushpa Colony, all owned by Christians, all descendants of the Portuguese who once ruled Goa and owned Bombay. The quiet of this peaceful colony of decent house-holders was rent only by the shrill whistle of trains that sped close by, heading from Churchgate to Borivali or Virar and in the opposite direction.

The owner of the cottage was one Mr Peris, and his sister-in-law Mrs Lucy Sequeira ran the school next door. “Welcome Mr Ghosh, be our tenant from today,” she said, handing me the keys. I was puzzled as I had yet to discuss the financial terms. Boudi cleared my doubts by saying that she had already paid three months’ rent in advance.

I had arranged for the house to be painted. Seeing me, Mrs Sequeira walked across. “Good you are getting it painted Mr Ghosh, Ali didn’t do it,” she said.

“Who Ali?”

“You don’t know Mumtaz Ali? He was a respected actor-dancer of Bombay Talkies.”

“Mumtaz Ali!” I was taken aback. “Of course I have seen him in the Bombay Talkies films during my college years. I was quite taken up by his dancing.”

“Right, Mr Ghosh!”

“Particularly in the song Main Bambai se dulhan laaya re, O babuji...”

“Right, right Mr Ghosh!” Mrs Sequeira nodded. “That same Mr Ali was the previous tenant. But he was going through hard times and couldn’t pay the rent. Six months had passed, so we had to send him a lawyer’s letter…”

“And the rent?”

“That we have waived. He is after all a respectable artist, with wife and two sons and two daughters…”

I was saddened by this bit of news. But already we were experiencing that lows were as much a part of life under the arclights as the highs. So, in the days that followed, when Mehmood used to come and ask for “a few rupees Dada!” I could never say “No”. Mehmood had an elder sister, a younger sister named Minoo, and two brothers. And income? Zilch. They had moved to a tenement near the station, and Mehmood would perch himself on a culvert nearby and seek an extra’s role from anybody from the industry who happened to pass by.

When casting for Do Bigha Zamin started, I suggested to Bimal Da, “How would Mehmood be for the role of the puchkawala?”

“Right,” Bimal Da agreed. He too knew Mehmood and his father.

That’s how he came to play the puchka seller who woos the grand-daughter of old lady who owned the basti. And as it happened, Bimal Da directed me to play another minor character – that of a kulfiwala.

Rajlakshmi as the owner of the basti and Nabendu Ghosh as the kulfiwala

Bimal Da was choosy when it came to casting. The managers used to line up many junior artists but as the director he would often mark out one of us from his team to act in a particular scene. Asit Sen, his chief assistant since his New Theatres days, was most consistently seen on screen. Bimal Da was also aware that I used to regularly perform on stage. Perhaps that is why he pitted me against Mehmood. Both of us were constantly trying to woo the basti owner’s granddaughter – he with puchka and me with kulfi…

Translation: Ratnottama Sengupta

Dharti kahe pukar ke is one of the several timeless songs in the film

******

Ratnottama Sengupta on how Two Acres of Land ushered neo realism on Indian screen

“We were rolling off the chairs when Nabendu Kaku played the kulfiwala in Do Bigha Zamin,” Rinki Di wrote in 2007 to greet him on his 90th birthday. The eldest born of Bimal Roy’s children had recorded her “great surprise at and admiration of” the screenplay writer’s acting talent. “His cameo as the rowdy village drunkard in Basu’s Teesri Kasam made us think it was cinema’s loss that he did not act more often.”

Bimal Roy’s casting won half the battle in ushering realism at a time when heightened drama – if not melodrama – ruled the Indian screen. In his debut film itself he had worked wonders with unknown names like Radhamohan Bhattacharyya and Binata Rai. If Udayer Pathey had introduced us to Socialist Realism, Do Bigha Zamin was to spell the dawn of neo-realism much like Bicycle Thieves did in Europe. This comes to the fore through the various accounts of those who had breathed life into the characters of Shambhu Mahato, Parvati, Laloo Ustad.

Jagdeep and Ratan Kumar in Do Bigha Zamin

When Joy was shooting for Remembering Bimal Roy, his Centenary Tribute to his father, Jagdeep had recounted that the director had asked him, “Have you noticed how a shoeshine indicates to his customer, who might be reading a newspaper, that he has finished shining the first foot? He just taps with the brush to indicate the other foot should be placed on the box.” And the young actor had grasped that he simply had to do ‘thak-thak-thak.’

On his part, Jagdeep had added fizz to the role albeit with the director’s nod. Instead of a straightforward ‘Give your shoes a super shine’ he chimed out “Kalkatte mein aiy ke, polish na karai ke, chale nahin jaana…” It parodied a hit song of the times, Ankhiya milai ke, jiya bharmai ke, chale nahin jaana from Ratan (1944).

Jagdeep had learnt his first lesson in realism on the sets of DBZ. He had not imagined that costumes for a movie – always a glamorous affair – could be bought in the flea market, then washed and scrubbed to make them look worn out.

******

“It broke my typecasting in mythological films.” – Nirupa Roy

Nirupa Roy had exactly the same experience with washed clothes as Jagdeep. “Our dresses were bought in Chor Bazaar since new clothes, even when washed, would not look worn out,” she told me in 2004, when I spoke with her to mark the golden jubilee of DBZ. The senior actress had by then become a Bollywood super mother for whom the iconic dialogue had been delivered in Deewar: “Mere paas Maa hai!”

“None of these would have happened if Bimal Da had not cast me as Parvati. It broke my typecasting in mythological films. Prior to DBZ, outside the studio people used to fall at my feet as I was seen only in the roles of various Hindu Goddesses. This was the first time I was playing a farmer’s wife and I got to express a range of expressions.

“More importantly, Bimal Da’s direction taught me to go behind the scenes, into the mind of the character. One day I had nail polish on my feet. Bimal Da asked me, ‘You have lived in a village, have you seen any farmer’s wife wearing nail polish?’ I had not expected the nail polish to come in the way of the scene as it was on my feet – and in any case films then were in B&W. But Bimal Da said, ‘Will it let you forget that you are Nirupa Roy, and become Parvati Mahato?'”

That care for the reality of a character had moved the director to call for an eyebrow pencil and thicken the leading lady’s fashionably trimmed brows, she had recalled.

Bimal Roy’s eye for detail ensured everything, from the sets to the clothes. “And the situations were so realistic that Balraj Sahni, who was in his earlier years a Hindi professor at Santiniketan, would go and sit in the tea stalls to chat with rickshaw pullers who were perhaps taking a break.” The lead actor would observe the way they wore their dhoti, placed the gamchha on the shoulder or wiped their forehead with it. How they folded their legs when they got to sit. “The tea adda was his classroom – it provided him with an insight into their lives. He actually practiced pulling the rickshaw, racing with it as much as how to bring it to a stop,” Nirupa ji had narrated.

No wonder his talent came to be respected worldwide after DBZ. And he came to be acknowledged as the most realistic actor of the Indian screen.

******

The despotic zamindar essayed by Murad

The despotic zamindar essayed by Murad was a stereotype that was not uncommon in films, before Independence or after we became a Republic. Bimal Roy himself came from a family of zamindars who ruled Suapur in East Bengal even after the partition of 1905. But he was cast in the socialist mould. So, the villain in Udayer Pathey/ Humrahi (1945) too was the rich father and his spoilt son who robs writer Anup of his due credit and fame.

DBZ was not the first and last Bimal Roy Productions film where a zamindar grabs what he lusts for – land, mansion, or a beautiful belle. In Biraj Bahu (1954) he had cast Pran as the quintessential bad man of the post-Independence years – a rich, handsome and lecherous zamindar. This was a role Pran re-enacted as Ugra Narayan in Madhumati (1957), a good-looking scion of the landed gentry with taste in White Horse whisky, chess and nautch girls in his relaxation hours, and willing to use force on any woman who caught his fancy!

However, the legendary director had not copied the characters from tales told and retold. One of his own ancestors had served as his prototype for the roles into which Pran breathed life, I had learnt from Boltu Da. This nephew of Bimal Roy, then in his eighties, had shared that “a Kali temple on the premises of the ancestral house which I visited in my infancy was frequented by the village women. But many women stayed away as Chhoto Dadu (grand uncle) had a roving eye. This was a stark contrast to his elder brother (who was BR’s father).” Boltu Da was once in the same horse carriage with a beautiful woman who, as he recounted, “had been abducted by this ancestor of ours. So I could readily identify with the character played by Pran in Biraj Bahu or Madhumati.”

By depicting zamindars as greedy womanisers, or the money-lending land-grabber of Do Bigha Zamin, Bimal Roy, much like Tagore, was clearing a ‘debt’ incurred in the past by his forefathers.

******

A wall in Jyoti Chowdhury’s home displaying Salil Chowdhury’s photographs and film posters (Pic: Ratnottama Sengupta)

Jyoti Chowdhury remembered watching Nirupa Roy do her makeup, and Balraj Sahni as he prepared for his work. In 1952, soon after Jyoti Kakima had married Salil Chowdhury, he was in Bombay to finalise the script of DBZ. Then he had returned to Calcutta where she was studying at the Govt College of Art and Craft. “We went again during the Christmas break, and that’s when I spent two weeks in the makeshift guest room next to Bimal Da’s office in Mohan Studio. The meals came from an Irani hotel across the street. That room with a three-fold mirror and other paraphernalia also served as Nirupa Roy’s makeup room.”

However, as an art student, she was more intrigued by Balraj Sahni’s costume. “He was always clad in a saffron dhoti. Curious to know why he did not wear the usual white, I learnt that on the B&W screen that colour would look closest to a soiled dhoti a rickshaw puller would normally wear.”

Bimal Roy, having started behind the camera, had an in-depth understanding of the impact of light, shade, and their interplay. This had come to the fore once, when he was meeting his artist cousin Abani Sen in Delhi.

“How can you create any visual impact with only Black and White?” asked the artist who had mastery over primary, secondary and every permutation of these colours. The generally reticent director had walked across the courtyard, picked up some bricks lying in one corner, arranged them in the sunlight, and invited his cousin. “Come, tell me, how many shades of grey do you see here?”

******

Shambhu ferrying the two little girls to school on his rickshaw

For a creative – nay, visionary – director like Bimal Roy, technical innovations like placing the camera on a jeep to track the breathtaking race between man and horse may have come naturally. But the realism we admire 70 years later does not rest on them or the shades of grey alone. The film’s core strength lay in capturing the reality of a newly independent nation that was mutating from agriculture to industrialization. That had spurred urban migration – a phenomenon that continues to grab headlines to date.

The rickshaw in art: Painting by Ajay De – Esplanade, 30×40, charcoal on canvas (Pic: Ratnottama Sengupta)

And the rickshaw puller? Calcutta, which had probably forged the earliest link with China, was the first city in the land to get rickshaws, tram cars, and metro rail. Yet, the rickshaw continues to be identified with the city where, six decades ago, I was taken to a primary school daily by an appointed rickshaw.

“Even as we boarded a bus after watching Bicycle Thieves, Bimal Da had made up his mind to make a film that would capture the reality of the Indian people,” Hrishikesh Kaku had said to me when I interviewed him in 1985 for The Telegraph. “That is why we – all of us dead tired and tense after working all day on Parineeta at Bombay Talkies – would go to Mohan Studio. I was editing Parineeta, and because I had scripted Do Bigha Zamin, I was also the Chief Assistant here. We were all bent upon projecting a tale of humans tossed by situations beyond their control – social or political. That is what earned Bimal Da his place in world cinema.”

This is how the realism of De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, shot mostly in natural light on footpaths of Italy came to stay on the Indian screen. And it comes full circle now when a restored avatar of DBZ plays before viewers in Venice on September 4.

More Must Read in Silhouette

The Making of Maa: Bimal Roy’s Debut in Bombay

‘Bimalda Spread Happiness’ – Jagdeep on Bimal Roy

And They Made Classics – Director-Writer Duo of Bimal Roy and Nabendu Ghosh

Bimal Roy: The Eastern Mystic Who Made Films

Apni Kahaani Chhod Ja: Leave a Story That Will Be Retold

Devdas – Fired by Love Sublime

‘Feelings, Lyrics, Orchestra — Everything was Different in Salil Chowdhury’s Songs’: Jyoti Chowdhury

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.

Respected Smt Ratnottama Ji,

I am so grateful to you for penning such beautiful article about my favorite film Do Bigha Zamin. For the first time I watched Rajya Lakshmi Ji ,who played the owner of most of the shanties. Her get up and natural acting as loud mouthed, but internally benevolent lady much impressed me. Later I saw her in Bandish & perhaps in Luku Churi. Selection of the unsung actor Sailen Bose, a Bengali actor from Bombay as Tea seller, who later appeared in Sujata and Devdas and Mr. Misra as Munim of Mr Murad, is indicative of the fact that eminent film maker Bimal Babu was very particular about the casting of even small characters.

Mr Paul Mahendra was a multifaceted artist, who could write /act and because of his clear diction was a dialogue director too. His booming voice was another asset, when he performed as an actor. His performance as uncharitable lawyer was simply magnificent. Ma’am I Thank You once again for your brilliant article and also introducing the Kulfi seller (Respected writer Mr Nabendu Ghosh) which gave me ample happiness.

Regards.