The Hemant-Salil alliance created a massive impact on the collective Bengali psyche through their songs together. Antara and Sounak explore the timeless Bangla songs created by the duo – Hemanta Mukherjee and Salil Chowdhury.

Note: Though Bengal spelt his name as Hemanta Mukhopadhyay/ Mukherjee in keeping with the Bengali pronunciation, for this article we refer to him as ‘Hemant’ to keep continuity with the book The Unforgettable Music of Hemant Kumar.

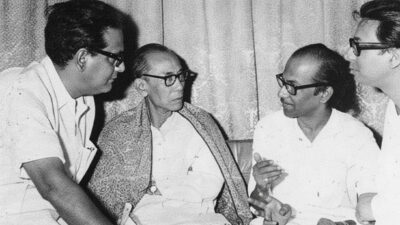

Salil Chowdhury with Hemanta Mukherjee

The official inauguration of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India, in 1943, coincided with the year of the Great Bengal Famine (known as Ponchasher Manwantar, the Bengali year of the famine being 1350). The year 1944 had IPTA staging Bijon Bhattacharjee’s play ‘Nabanna’, under the direction of Shambhu Mitra, which came as a clarion call, initiating a new era of Bengali theatre. The days of ‘art for art’s sake’ faded away in the social turmoil of the era that followed, surreptitiously giving expression to a new urge to live a life of self-sustenance.

The years following the Great Bengal Famine saw some of the most important happenings in the political history of Bengal, including the Bengal Riots (1946), Tebhaga Movement (1946), and Partition of Bengal (1947). The IPTA played an important role in these turbulent years as a revolutionary platform, initiating mass awakening through cultural activities. Apart from Bijon Bhattacharjee, Shambhu Mitra, eminent personalities like Hemango Biswas, Jyotirindro Moitro, Debabrata Biswas, Salil Chowdhury and Suchitra Mitra were active members of the IPTA then.

Hemant Kumar, by the latter half of the ‘40s, became a part of the IPTA programmes. This marked the beginning of one of the most illustrious periods of Hemant’s musical career. His association with Salil Chowdhury created a massive impact on the collective Bengali psyche through their songs together.

The writer, poet, composer, and singer

Salil, still in his early twenties, was an active member of the IPTA. He was igniting a kind of energy, composing songs of mass awakening that were resonating across Bengal, in the voices of the IPTA singers. The songs spoke about the sad plight of the grassroots people, struggling hard to make ends meet such as the farmers, boatmen, fishermen, workers and palki-bearers, creating powerful imagery through words and music. Songs such as Dheu uthhchhe kara tutchhe, Aayre o aayre, Hei sambhalo dhan ho, O alor pathojatri, and others, several of them with Hemant Kumar, are remembered even to this day.

Their iconic association started with a song that went on to become one of the most loved songs of all time. One fine day, Salil came up to Hemant, hoping that the singer would record one of his compositions. This was in 1948. The Communist Party had just been banned by the Government of Bengal (the ban was lifted before the first general elections in 1951). To continue his musical journey, on the suggestion of the party, Salil had joined the Gramophone Company as a lyricist and music composer.

Sitting in Hemant Kumar’s house at Indra Roy Road, Calcutta, Salil sang, one after the other, his compositions for the IPTA, winning more and more appreciation from the singer. However, Hemant made it clear that these songs were meant for choral singing, and he would not be able to sing these as solos. As Salil was about to leave that day, he recalled his latest composition which was only half composed as of then. Hemant heard the song and was thrilled. “This is the perfect song for recording. Write the second half and bring it soon,” he said.

The same evening Salil wrote the second half of the song, and also set it to tune. The song was Gaanyer Bodhu, (gaanyer or gnayer means village and bodhu means a married woman or bahu) the life-story of a farmer’s wife; the first part of it, describing her happy days in the village with her husband, and the second part, describing how her life changed as the Great Bengal Famine set in, and the social reality of the days shattered all her dreams. Salil described allegorically, the root cause of the Famine as,

Dakini jogini elo shato nagini, Elo pishachera elo re

The blood-thirsty witches, the venomous snakes, and the demons came in hordes

Shato pake bandhiya nache ta ta ta dhiya nache re

They danced, twisting, turning, stomping

Kutilero montre shoshonero jontre gelo pran shoto pran gelo re

In their spell of deceit and exploitation, hundreds of lives were lost.

The music also distinctly divided the song into two parts—the first part being a soft, romantic, dreamy tune which starts spinning the story of a loving, contented village woman; the second part, a rapid, racing tune expressing the sudden wave of destruction that sweeps away everything. The vivid imagery in the song could make every listener visualise the story which began as

Kono ek gaanyer bodhur kotha tomai shonai shono Rupokatha noy shey noy

(Let me tell you the story of a village woman, it’s not a fantasy)

Hemant Kumar’s voice reached, connected with and impacted every Bengali listener, in every corner of Bengal and among Bengalis living outside of Bengal.

Gaanyer bodhu (Non-film, 1949) Salil Chowdhury / Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Gaanyer Bodhu record (released July, 1949)

Gaanyer Bodhu, released in July 1949, marked the beginning of a new era of Bengali songs, with the advent of realism in recorded music. Hemant Kumar, who was already famous for love songs like Kotha koyo nako shudhu shono, became the voice of the masses. Romancing, in the social context of the ‘40s, was too expensive a luxury to afford and young lovers deeply identified themselves with the words of poet Sukanta Bhattacharjee, Purnima chand jeno jholsano ruti, which meant that the full moon seems nothing but a half-burnt roti. Gaanyer Bodhu turned Hemant into the most adored name in the arena of Bengali music. Following the huge success of this song, Salil Chowdhury and Hemant Kumar worked on many more Bengali songs and not surprisingly several of these became cult songs.

Salil next put to tune the largely-realist poet Sukanta Bhattacharjee’s Anubhav 1940 (Abak Prithibi) and Anubhav 1946 (Bidroho aaj bidroho charidike), and Hemant sang both on record. This, released in July 1950, was the first record of Hemant Kumar which mentioned the name of Bharatiya Gananatya Sangha (IPTA) on the label and the songs were presented as ‘Bengali Patriotic Song’ (unlike Gaanyer Bodhu, which was described as a ‘Bengali Modern Song’). The first of the two songs reflects the heart-rending cry of the Indian masses living under the oppression of the British, and the second reflects the glorious upsurge of Indians against the imperial British rule.

In September 1951, Hemant Kumar recorded Runner, again a poem of Sukanta, set to music by Salil Chowdhury. This song, described yet again as a ‘Bengali Modern Song’, describing the pain and relentless toil of a village runner (as postmen were then known) who runs through forbidding jungles in the sleepless dark nights with a sack of letters on his back, ringing his little bell and braving cold, rain, hunger and wild animals. Needless to say, the song rose not only in popularity but also became a cult song inspiring listeners to spare a thought for the poor and deprived.

Bengal’s Music Makers: Hemant Kumar, SD Burman, Salil Chowdhury and RD Burman

In the following years Hemant and Salil worked together to present songs like Nouka Bawar Gaan, Dhan Katar Gaan (both described as ‘Bengali Progressive Song’ on record label), Palkir Gaan (penned by poet Satyendranath Dutta). These were the earliest instances of recorded songs which reflected the ‘flow of life’ through the journeys of common people (especially the deprived sections) like the runners, farmers, boatmen, palanquin bearers, etc and striking out a different path from the common trend of popular songs, mostly love songs. These songs were written and composed in the socio-cultural backdrop of Bengal, yet they gained great popularity outside the state.

In fact, soon after the release of Gaanyer Bodhu in 1949, Hemant Kumar had to sing a Hindi version of the song, translated by Madhukar Rajasthani, titled Gaon Ki Raani.

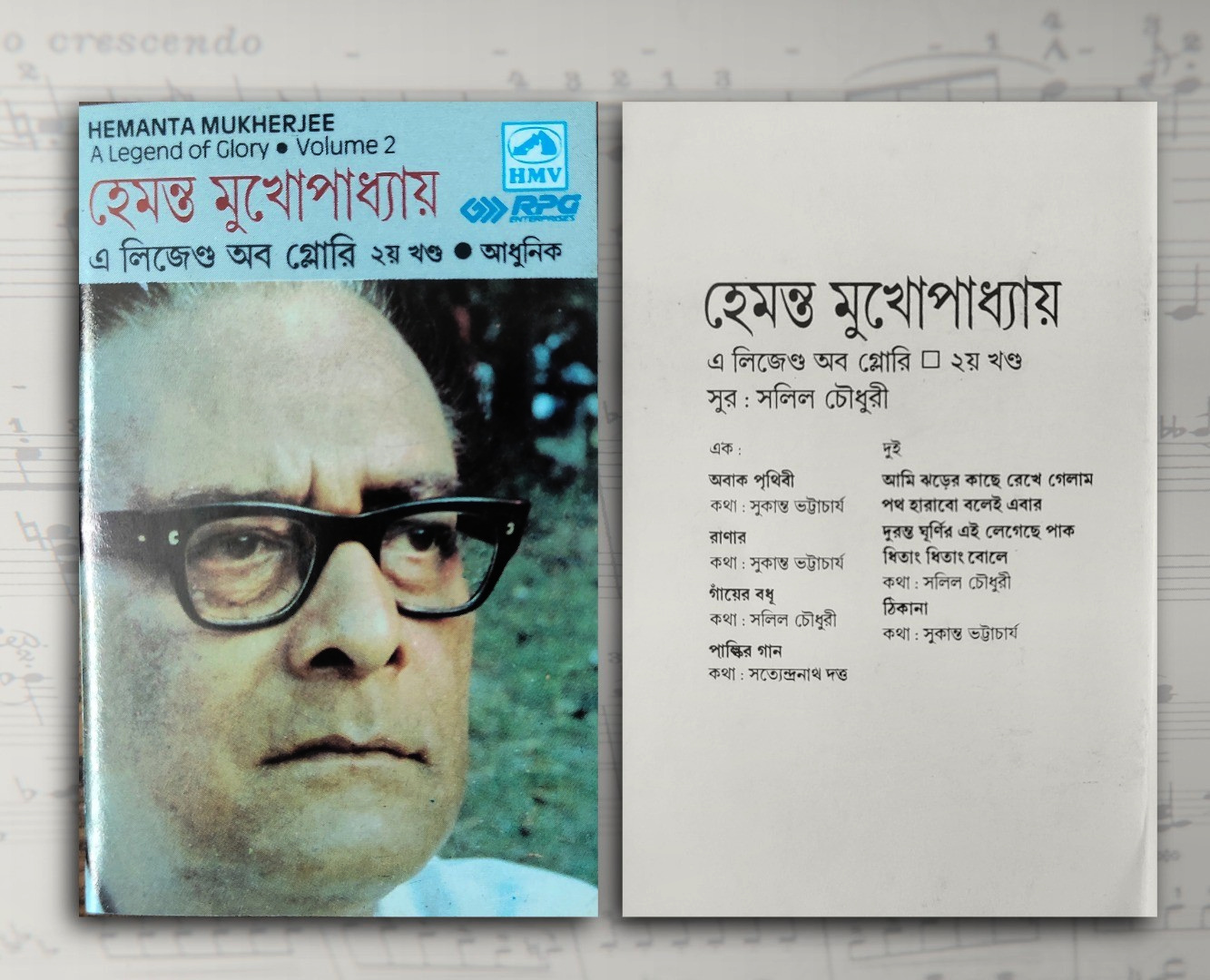

HMV’s 4-cassette collection of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay’s songs – ‘A Legend of Glory’ dedicated Vol 2 entirely to his songs with Salil Chowdhury

Some of the everlasting songs the Hemant-Salil duo created include:

» Abak prithibi & Bidroho aaj (Sukanta Bhattacharjee/Salil Chowdhury, 1950)

» Dhan katar gaan (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1951)

» Palkir gaan (Satyendranath Dutta/Salil Chowdhury, 1952)

» Pathe ebar naamo saathi (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1954)

» Dhitang dhitang bole (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1955)

» Duranta ghurnir ei legechhe pak (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1958)

» Path harabo bolei ebar (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1958)

» Ami jhorer kachhe rekhe gelam (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1961)

» Moner janala dhore (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1961)

» Shono kono ekdin (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1969)

» Amay proshno kore neel dhrubotara (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1969)

» Thikana (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1970)

» Rabindranather proti (Sukanta Bhattacharjee/Salil Chowdhury, 1981)

» Jete jete poth bhulechhi (Salil Chowdhury/Salil Chowdhury, 1982)

Amay proshno kore neel dhrubotara (Non-film, 1969) Salil Chowdhury / Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Excerpted with permission from the Chapter ‘Bengal’s Immortal Singer-Composer: A study of his Bengali film and non-film music’ by Antara Nanda Mondal & Sounak Gupta from the book The Unforgettable Music of Hemant Kumar, by Manek Premchand (Blue Pencil, 2020)

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.

Lovely pleasure reading and listing to Hemant ji songs my all time favorite till date.

Ssunita (Raj khoslajis daughter)

Sunita ji,

Thank you so much for the feedback! 😊🙏 Yes, Hemant Kumar’s songs are evergreen. And how can one ever forget his timeless songs in Raj Khosla ji’s movies – ‘Hai apna dil to aawara’ is still an anthem for the youth. Or the soft, romantic tandem with Lata – ‘Yeh baharon ka samaa, chand taaron ka samaa’.