& Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel  & Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel

Among the memorable dances picturised in Hindi films, Bol ri Kathputli from Kathputli (1957) is an innovation in terms of choreography and music. Anand Desai (in maroon font) and Antara explore the finer nuances of this exuberant story of the puppet personified by Vyjayanthimala, written by Shailendra, composed by Shankar Jaikishan and sung by Lata Mangeshkar

The story of dreams and aspirations of a puppet

Song: Bol Ri Kathputli (Happy Version)

Film: Kathputli (released 4th October 1957)

Directors: Amiya Chakrabarty and Nitin Bose

Music: Shankar Jaikishan

Lyrics: Shailendra

Singer: Lata Mangeshkar

Starring: Vyjayanthimala, Balraj Sahni and Jawahar Kaul

It’s a simple, roadside puppet show. The traditional royally decked up Indian Rajasthani puppets are busy doing their tango making their young audience burst into giggles. Amid those excited kids is a doe-eyed, impetuous young girl, munching chanas and watching every move of those dancing puppets.

The music reverberates with a verve and zing in it. Curious to know who is making them dance, the girl peeps below the curtains of the tiny puppetry stage and her eyes meet the surprised puppeteer.

You can’t blame the beautiful girl for getting into the mood and decide to replicate the puppets herself with a dance that takes your breath away. And what is it about? It’s a dance to introspect, to convey one’s own innermost aspirations as the dreams of a kathputli (puppet) through a conversation with the kathputli! Yes, there are layers in this seemingly innocuous song and astonishing dance.

Bol ri Kathputli has two versions – the happy one which we explore in this essay and a pathos-laden version too which comes later in the film.

The puppet show over, the impish girl finds herself still in the mood of the dancing puppets and starts personifying the kathputli

The entire 2.29 minutes of the Pre Music {as we loosely may call ‘before the prelude’} is based on a 6/8 beat followed by a 4/4 beat. The main song has a 4/4 and a 2/2 beat.

Catch the beauty of the almost similar bars used by SJ on a Piano in Sangam {1964} for the song Har dil jo pyaar karega from 4.43. till 5.01. (This similarity was pointed out by Falguni Desai. Watch the clip at the end of this essay)

Music maestros Shankar Jaikishan’s composition based on Raag Kirwani, used an assortment of instruments including Khanjari, Chakola, Mandolin, Bongos, Lead and Rhythm Violins, Accordion, Cello, and Piano.

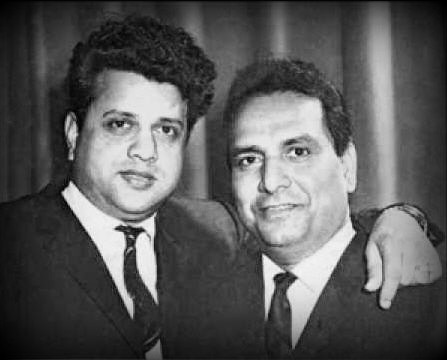

Shankar Jaikishan (Pic: Google Image Search)

Shankar Jaikishan came up with a masterpiece of an arrangement here, making the Bongos sound like the Cajon – flattish, allowing the other strong percussion to emerge as dominant. Sebastian in all his glory used Cello’s and Piano to support the Violin obligato counter melodies.

The puppet show over, the impish girl finds herself still in the mood of the dancing puppets. Music is in her bloodstream, rhythm in her nerves. Finally not able to stop herself, she breaks into an impromptu dance, personifying the ‘kathputli’.

This song has the longest Mukhda entirely without a kafiyaa.

Just see how Shailendraji has created a question answer song between a human and an inanimate object, a doll. And all through the lady asks

Bol ri kathputli dori kaun sang baandhi

Sach batla tu naache kiske liye

And pat comes the reply from the kathputli:

Baawri, kathputli dori piya sang baandhi

Main naachoon apne piya ke liye

A delightful conversation ensues, weaving the dreams and aspirations of a puppet. What if she is a puppet? She has a heart too that yearns for love.

What an expression of sublime happiness

jahan jidhar saajan lejaaye sangh chalu main chhaaya si…

woh hain mere jaadugar mein jaadugar ki maaya si…

jaan boojhkar chhed ke mujh se

poochhe ye sansaar

Notice the brilliant kaafiya… “saaya si” and “maaya si“.

Kids gathers around the exuberant dancer as the story of the puppet brings out the child in her

And Kaviraaj takes us back to our childhood phrases – “Sach-mooch” which we always used colloquially between friends and words such as “Khaali peeli”. It’s a total recall of childhood exuberance and mischief.

The 29 seconds intro has three arrangements – first 10 seconds from 2.30 is a slow and a pensive Accordion build up with Mandolin jitters. Then for the next 19 seconds from 2.48, the Violin Sautille’s, Khanjari and Bongos take precedence and finally, the last 9 seconds have the Accordion, Bongos and Khanjari.

The Bongos and the continuous Khanjari match Vyjanthimala’s dancing style – the Bongo’s staccato roll at the beginning of the M1 [4.40], and two strokes to end it with an Accordion bridge [ 4.45 ] is a work of Art.

The puppeteer (Jawahar Kaul) is surprised and charmed at the way his little puppet show has affected this girl

Vyjanthimala, an accomplished Bharat Natyam dancer has shown her excellent skills in the staccato hand and body movements to resemble a Puppet. Incidentally very few trained Bharat Natyam dancers adopted it in its purest form and Vyjanthimala was one of them, according to Namita Bodaji, an accomplished dancer of International repute.

The dance that illustrates this story of the puppet is unique and effervescent. It looks like relatively easy, unaffected dance but it isn’t. She is impersonating a puppet and hence all the malleability and fluid rhythm of a regular dance or a classical dance is replaced by mudras that need arms to be and hands folding at angles – stiff but in perfect harmony with the beats. Her eyes speak a thousand words as she hops, skips and jumps and even tumbles once, hurting her foot.

Lost in her own world of imagination, oblivious to the amused passerbys collecting around her, she drapes a shawl hanging on a fence on to an overturned pot on the fence that has a face painted on it. She puts a scarf around its head and draws a moustache, making it personify the ‘saajan’ of her story. Amid the increasing crowd is the puppeteer who is surprised and charmed at the way his little puppet show has affected this girl.

She puts a scarf around its head and draws a moustache, making it personify the ‘saajan’ of her story

Kaviraaj then uses the beauty of rhythm in his words.

Shankar Jaikishan with Lata Mangeshkar (Pic: Songs Of Yore)

piya na hote mai na hoti

jeewan raag sunata kaun

pyar thirakta kiski dhun par

dil ka saaj bajata kaun

o o o door door jis chaman se guzre

gaati jaye bahar

coming back to the refrain again – bol ri kathputli dori

The unique and brilliant Sanchari from 5.01 till 5.07 in M3 is the surprise element. The Mandolin bridges between the antara lines are also lovely. And so is the Mandolin open string pizzicato from 5.44 till the fade out at 6.03. The rest of the song flows in a standard pattern.

Shankardas Kesarilal popularly known by his pen name Shailendra

(30 August 1923 – 14 December 1966)

This amazing song composed written by Shailendra and sung by Lata Mangeshkar was the title song of the film Kathputli, in a ‘Pygmalion’ type of story with a love triangle. The naturally talented singer-dancer Pushpa is all eager to assist the puppeteer Shivraj with his roadside puppet show. But when he meets with an accident and some of his dolls are also broken, she approaches Loknath for some stage assignments. He spots her talent and wants her to be a movie star. In his attempt to shape her career, he ends up being a godfather and trying to control his protégé’s emotions and life. The playful personification of Kathputli starts getting manifested in real life for Pushpa.

Kathputli, was directed initially by Amiya Chakrabarty and later completed by Nitin Bose on the request of Mrs. Amiya Chakrabarty, when the director passed away during the making of the film. At that time Nitin Bose was busy directing Joga-Jog in Calcutta and had to keep shuttling between the two cities. Both these stalwart directors had their own individual styles of filmmaking in their illustrious careers. But Bose tried to retain Amiya’s style of filmmaking to ensure consistency in the film and thus despite a change in the captaincy midway, the film emerged a hit.

And at as an end note, we must share a few words about these two stalwart filmmakers who never had the chance to discuss the film but it did emerge as a finely sculpted creation.

Nitin Bose

(Pic: Nitin Bose: Flowering of a Humanist Filmmaker – an NFAI publication)

A former political activist who was held during the Salt Satyagraha, Amiya Chakrabarty had to leave Bengal and he joined Bombay Talkies. His films Jwar Bhata (1944) catapulted Dilip Kumar into stardom and Daag (1952) cemented it further. Vyajayantimala in Kathputli (1957), and Nutan in Seema (1955) are two more star-maker superhit films in his brief career.

Nitin Bose on the other hand, is credited for a path-breaking innovation – the introduction of playback singing in Bhagya Chakra (Bengali) and its Hindi version, Dhoop Chaon (1935). Dilip Kumar’s Ganga Jamuna (1961), directed by Bose is one of the biggest blockbusters. He is also the one who introduced Uttam Kumar in Drishtidaan (1948) and directed the Dilip Kumar-starrer Milan, based on Tagore’s Naukadubi. Another superhit was a story of unfulfilled love, Deedar (1951) starring Ashok Kumar, Dilip Kumar, Nargis and Nimmi.

Understandably, the film Kathputli was in safe hands even if the boat rocked midway.

More to read in The Song Story

Unko Yeh Shikayat Hai Ke Hum Kuch Nahin Kehte – When Silence Speaks Volumes

Love is… Claiming Rights: Teri Zulfon Se Judaai to Nahin Mangi Thi

When Cinema Matched Music Beat by Beat: Nadiya Kinare in Abhimaan

The Mesmerizing Moods of Jaane Kya Tune Kahi (Pyaasa)

The Tender Musical Tête-à-tête in Chupke Se Mile (Genius of SD Burman)

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

We are editorially independent, not funded, supported or influenced by investors or agencies. We try to keep our content easily readable in an undisturbed interface, not swamped by advertisements and pop-ups. Our mission is to provide a platform you can call your own creative outlet and everyone from renowned authors and critics to budding bloggers, artists, teen writers and kids love to build their own space here and share with the world.

When readers like you contribute, big or small, it goes directly into funding our initiative. Your support helps us to keep striving towards making our content better. And yes, we need to build on this year after year. Support LnC-Silhouette with a little amount – and it only takes a minute. Thank you

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.

Perfect (as usual- we can’t expect anything less now!) analysis of a hauntingly catchy song. In fact after all these years two songs from this movie (Manzil wohi hai – is the other) instantly whisk me back on a nostalgic tour to a golden period.

As pointed out above there are two versions -the seemingly simple one at the start and the dhudm-dhudum reprise at the climax. The reviewer of that period, Filmfare I think, said that S&J appeared to have lost their touch and only in the last song they recovered it. I totally disagreed then and more so now.

The first song with its economic accompaniments thus giving Lata’s sweet voice its full space is only seemingly simple .On the contrary it is S&J at their cunningly creative best. Nowadays I just close my eyes let the song take over.

Thanks Antara and Anand for your lovely article!

Thanks Bharat ji,

A bit late in the day to say thank you! But your comment is always one I keep coming back to as it offers insights that have escaped me earlier.

Agree with you, the two songs in this film particularly are in a class of their own. Analysing this song drove me towards the unique history behind it, of two directors doing the film and yet maintaining a consistency.

Thanks to Anand ji, I got an absolutely new look at an ever favourite. 🙂

Natmastak Bharat bhai