The quick paced usage of such stock monochromatic films seemed to allow Ghosh to situate Samaresh Mazumdar’s 1980’s novel Kalbela, cinematographed ( initially planned for the Doordarshan ) in 2007 within the matrix of a period-piece, yet it transcends the confines of a period-film.

Emblematic moments of an angry desperate Kolkata of 1968-70, the iconic shots of Mrinal Sen’s Calcutta’71, Interview and Ray’s Pratidwandi are followed by a self-reflexive tone of the protagonist as Gautam Ghosh’s Kalbela unfolds with the words –‘The Kolkata of my youth has changed…’. The maker and the protagonist are rolled into one, as Ghosh confided in an interview later that, it was his ‘looking back at his youth’.

The event, the novel and the film are separated roughly by a gap of twenty years from each other. The event was that of some disenchantment with ‘order’. The novel weaved the encounter of an ideologically emancipatory narrative with the everyday flow of romance. The heroic vanguard Animesh is a new entrant to a turbulent Kolkata of 1970 from north Bengal, only to be drawn in the flow of radicalism and rage. Unapologetically apolitical Madhabilata rebels too, against the ‘order’ of the domestic to fall in love with a rebel. An ‘invisible’ rebel is born out of Madhabilata who could shoulder single-handedly the trials and tribulations of love at a difficult time. While the film of 2007, released commercially in 2009, stands as a pronounced gaze of the male protagonist ( or the director’s ? ) at the events of a volatile period of Kolkata.

The ageless iron buoy floating on the timeless Ganges contours urban Kolkata’s tryst with destiny. The flyover shot ends up with the visual of this buoy, it appears towards the end of the film also as Animesh’s tryst of being an agent of change has completed a circle. This visual at the beginning is resolved to its subsequent shot of two hands, a man and a woman’s, finding solace in each other’s comfort. The voice-over affirms that love has no ideology.

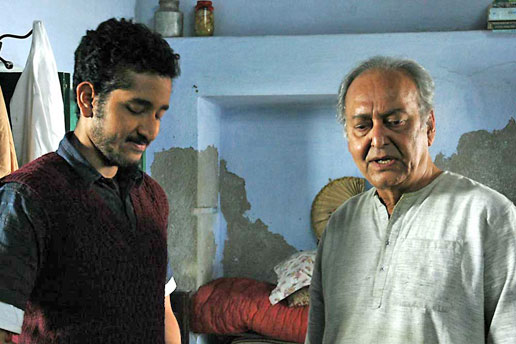

Gautam Ghosh’s cinematic treatment of Samaresh Mazumdar’s Kalbela winds up with the half-crippled brutalized Animesh getting solace in a bustee ( jhuggee ) room with his beloved Madhabilata ( the quintessential cult figure of a sacrificing and weathering Bengali woman ), the shot freezes with their love-son returning from school and perching between the two. At the backdrop hangs CHE’ s portrait from the walls of the shanty jhuggee room. Che’s portrait, symbolizing a loaded ideology in Madhabilata’s space of resilience may defeat the running theme that love has no ideology. That could be the dialectics of a young dream of love and change. The re-union setting was the year immediately after the installation of the left-front government / left regime in West Bengal.

Kolkata beyond the darkness years of the Emergency ( 1975-1977 ) resolved to cleanse itself of the scars of the state brutality inflicted on its soul and body. It was also a time of hope and expectation with the left-front government promising alms, if not the revolution. Che in a jhuggee wall is certainly not an anachronism for that. Yet, the maker has no obligation to make Samaresh’s Kalbela the mirror of a time. In abundance Ghosh has toyed with the sense of linear timing. In costly acrylic paints, in shinning red and black “ Make 70’s the decade of liberation “ could be a graffiti of post 1980s, yet that served a huge backdrop canvass in the film. The bygone ‘70s was the time for graffiti out of kerosene mixed black shoot or the asphalt pitch, written in unsteady hurried hands. Madhabilata puts on a double-bindi on forehead, a style which could hardly figure in the urban young woman’s style of 1970s. Not before the 2000s that the issue of Tagore’s Shantiniketan getting concretized could surface in the Bengali political discourse. The gradual decadence of the natural topography of the serene Shantiniketan as a result of real estate developers, yet could figure in the film. Madhabilata sharing this criticality with Animesh while on a hideout in Bolpur, trudging across the tranquil Sonarjhur forests. It was 1970. Ghosh does not care, as he has no obligation to narrativise the period only.

Samaresh Mazumdar’s Kalbela in mid 1980s appeared as a serialized novel in the most popular Bangla literary magazine Desh. Never like the present, yet the rumblings of a discontent within the left-circles in Bengal, especially in urban Kolkata started setting in. It was a unique period in more than one sense. The skeptics, who questioned the parliamentary path of the left, were intermittently spreading the words of disbelief in University campuses and in some labour lines. The emotional quotient of those who guided and supported the left to power in the state was also running high, trying to protect the hard fought battle in its favour. Mainly it was in the realm of ideas and utopias. The ground-reality hardly could bring people together, neither in their wilderness nor in any positive assertion. Still, the political study-circles flourished with their dissections of Marxist philosophy, Leninist programmes and Maoist strategies. Around that time Kalbela as a novel could only add to the emotional landscape of a generation who in their prime years experimented with the ‘war against the State’ to taste its logical defeat.

The Marxist-Leninist philosophy, the paradigm of developmentalism sustained itself with chinks growing within. The paradigm of criticism was bound to shift. The accumulated questions could take a nebulous form in and around the year 2006. With the 7th left-front government unequivocally championing the cause of industrial development, de facto celebrating the flow of private capital in real terms, the ‘other’ side joined hands from all quarters to form committees of various hues- from against land acquisition to protect indigenous lives of the people. In and around 2007, the events of rural Bengal gravitated cultural activists from taking to the streets of Kolkata to visiting and intervening at the very sites of state brutality. Another time, another emotion, another language of protest started reverberating the socio-cultural scenario of Bengal. Another audience is being prepared by the time itself who could get aroused to the dramatic events of Poshukhamar (adapted from George Orwell’s The Animal Farm ). This Arpita Ghosh’s drama during the same time, performed amidst an up-market locality Salt Lake city in Kolkata drew the same response of anger and distrust that the rural masses exhibited while watching Haranath Chakraborty’s Tulkalam (tr. The Bedlam). In open fields, with make-shift projection system thousands were glued to the trite dialogues of the film’s protagonist Toofan, who could melodramatically voice that there cannot be land acquisition for industrialization at the cost of people’s lives. Such spontaneous screenings of Tulkalam were occasioned as a result of unscrupulous blacking-out of its show by some distributors and theatre hall owners in some volatile parts rural Bengal. Exactly in this milieu Gautam Ghosh, a deeply politically embedded film-maker, scripts from the novel a cinema for a different Bengal of a different century.

The police lock-up brutality on Madhabilata – no, none, except a generation of politically inclined section, could relate to the ignominy of Archana Guha, who was picked from her house for interrogation for information of ‘absconding’ activists and subjected to continuous police torture in the early 1970. This case (one amongst many such) stood out as it finally resulted in a grim long-drawn protracted legal battle by her brother Soumen Guha, which resulted in the indictment of the most notorious police-officer Runu Guha Neogi. This symbolic association drawn by the observer problematises the constitutional resistance against state-violence. Yet, such possibilities are tangential to the random audience studied in this exercise.

The audience-reading retrieves the question from history- in this year of 2009, not many noticed the CHE portrait in the shanty bustee room. A cursory passage into many a bustee clusters in and around south Kolkata localities reveals that the idols of the goddess Kali or Durga are a passé in these bustee walls. Apart from the icons from the Mumbai dreamworld, it’s all about the colourful posters of Dada and Didi (affectionate vernacular coinages for the elder brother and sister). Random statistically, Dada is ahead of Didi. For this energized bustee dwellers of 21st century Kolkata Dada (Sourav Ganguly) has retired from international cricket. Didi ( Mamata Banerjee ) is still around promising ‘Ma, Mati, Manush’ ( an euphemistic treatise penned by Ms. Banerjee on the indigenous peoples’ contest for right to life and livelihood). Can a contemporary making of Kalbela accommodate a bustee ( jhuggee ) setting with Mamata’s portrait at the backdrop wall? It’s a crystal clear NO. That is the poignant opinion of a wide section of the urban elite audience surveyed. But a still larger section, outnumbering the articulate cine-goers, did not actually notice the Che portrait. They did not even bother or contemplate the question of whose portrait is hanging down the wall.

Albeit, both for the director and the audience, the encrypted Che like the iron buoy floating on the Ganges is equally timeless defying the historical march of the world-spirit. Instead of being the pure ‘becoming’of chronos , they are held within the topos of continual tension between the being and the not-yet-being. Che thereby might be at work as password, giving access to someplace else, a leeway drift toward a space of dream and resistance consisting of an indefinitely myriad of hues. Also Che as change in installments – equally timeless – an ad hoc attempt to retrieve the forgotten project of the unfinished humanity or the resurgence of the recurrent desire of the self for such. Beyond the dim-lit Nandan complex, beyond the stars in the end-winter Kolkata night-sky, another narrative unfolds not terminating into a closure.

(All pictures used in this article are courtesy the Internet)

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.