Ratnottama Sengupta travels back in time to the Wednesdays and Sundays and Fridays when school girls and college youths refused to trade their evenings with Ameen Sayani for plays or birthday parties. A personal journey through the golden age of radio and Binaca Geetmala.

Ameen Sayani in a pensive mood

(Rare photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

10, 9, 8, 7, 6… the countdown has begun. Tighten your seatbelts to take off in a time machine called Radio Ceylon!

Behno aur Bhaiyo! Binaca Geetmala ke sunanewalo ko Ameen Sayani ka namaskar…

There you go: three distinctive statements made in that one sentence. But how many decades has it taken for me to realize the significance of listening to a programme from 8 to 9 pm every Wednesday. A programme that had started before my birth – in December 1952, to be precise – and had continued till April 1994?

To begin with Behno and Bhaiyo: it clearly took off from the common English address of ‘Ladies and Gentlemen.’ “Dad used to say that the greeting was inspired by Swami Vivekananda’s famous address in the US where he greeted the Congress with the words, ‘Sisters and Brothers of America!'” recounts Rajil Sayani. This was revolutionary more than half a century ago, when patriarchal India was more used to hearing ‘Bhaiyon aur Behnon.’ My generation, perhaps because of the exemplary presence of Indira Gandhi, delighted that Ladies First had been made the norm even in that pre-Women’s Day world.

The almost-antique Murphy radio (Pic courtesy Ratnottama Sengupta)

Growing up in the family of a busy screenwriter of the 1960s, I used to be glued to the almost-antique Murphy Radio. The British brand was so loved not for its mascot Baby but for the songs, old and new, it brought to millions of us across the subcontinent. But in the days when there was no television, no video, no laptop, no YouTube and no WhatsApp, radio was not only about listening to songs – it was our only link to developments in the world of Hindi cinema.

Mind you, it was quite natural for us to be surrounded by talks of films and cine personalities. Still, I never imagined then, that one day I will make an identity for myself as a film critic, film analyst, film historian. Now when I look back, I realize that the founding of all these streams of love for the art, science and commerce of Cinema lay in the information I was soaking up like a sponge – from that formidable voice addressing Sisters and Brothers of the Sound Waves.

Ameen Sayani not only set a benchmark in radio presentation. His voice, at once friendly, engaging and forceful, was more than a member of the household. He was Radio Jockey before the word entered my dictionary. He lead me like Eklavya, without the guru’s knowledge – into assessing and ascertaining who’s the more worthy contestant. And he led me into loving Hindi. This, at a time when the language was modernizing itself by being neither Urdu nor Khadi Boli, neither hi-fi Sanskrit nor durbari Farsi.

A young Ameen Sayani

(Rare photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

Back then, I did know that Ameen Sayani had an elder brother in Hamid Sayani, who spoke impeccable English and conducted the Bournvita Quiz Contest with rare panache. But only in recent times I traced the source of his effective communication skill: He had grown up assisting his Gandhian mother in editing, publishing and printing Rahber, a multilingual fortnightly journal for neo-literates, from 1940 to 1960! Surely this grounding in simple communication helped Ameen Saab in producing 54,000 radio programmes, thousands of jingles, in compering stage shows, in essaying cameos in a number of films, and won him the Padma Shri in 2009..

Any surprise that, week after week after week, we would ‘Regret’ invitations to any birthday party or a celebratory dinner? We simply couldn’t miss the Geetmala Countdown, could we? So many of us would even create our own fehrist of favourite songs and wait to see if our prediction matched the countdown of The Ameen Sayani! And why just us, listeners? Music directors too closely followed the countdown.

“Once our radio broke down, and Baba gave it for repairs,” my cousin Shampa recalls their days in Shahjahanpur. “Every day after that Rana Dada would nag him to get it back before Wednesday. But when it didn’t materialize before the Geetmala countdown, Dada declared a hunger strike – ‘Roti nahin khana hai mujhe!’”

Makarand Waikar, producer-director of the documentary film, “My Radio My Life” had similar memories of Every Wednesday. “Everyone at home would gather around the radio and tune in to the shortwave band of Radio Ceylon ahead of time so as not to miss a single minute of his program.” And those who couldn’t make it to home in time? ”They would stop by a restaurant or shop to listen to it, ensuring they didn’t miss it at any cost,” he wrote in Indian Express when Ameen Sayani passed away last year, at age 91.

Ameen Sayani receiving the Padma Shri

(Rare photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

One result of listening so intensely to the Geetmala was that every time my school friends played Antakshari, I was sought after by both teams. And every time I tuned in to requests from Bareilly and Jhumritalaiya, Bijoy Da would say, “Have they consulted our Encyclopaedia Cinematica?” Doubtless my cousin was leg-pulling me. But I have no doubt he would have been proud when I wrote a chapter in Encyclopaedia Britannica – on Hindi films!

***

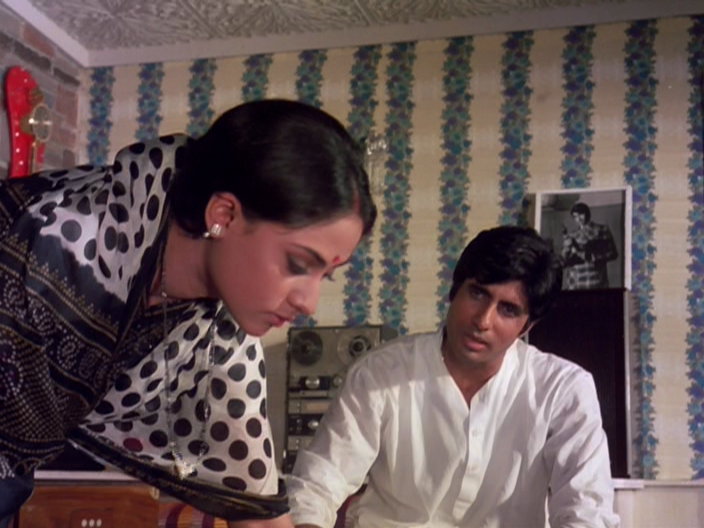

Ameen Sayani with Amitabh Bachchan (Rare photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

The unequalled popularity of Binaca Geetmala can be gauged from the reference to it in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Abhimaan. The Amitabh Bachchan Jaya Bhaduri starrer revolves around a star singer couple. One morning Chandru, their common secretary, delights at the success of Uma. Newly married to Subir, this new star in the musical cosmos has scored with four entries in the countdown. This triggers envy in the husband’s heart, who has stolen all the shows thus far.

Chandru says, “Mubarak ho Bhabhi, chhapake se tumhare chaar gaane Binaca mein aa gaye.” Subir adds sarcastically, “Itni badi khushkhabri sunne ke baad kam se kam ek Binaca smile hi de do” – the first cracks in their marriage. (Watch it here)

“Itni badi khushkhabri sunne ke baad kam se kam ek Binaca smile hi de do”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the countdown method combined the sale of record figures with the number of letters – postcards, to be precise – received from listeners. In Abhimaan, Chandru also makes an oblique reference to influencing the countdown, which was a high point of the year-end programmes, by “ensuring a massive flow of letters.”

At one point of time 65,000 postcards would pour into the office. Since these had to be stored for three weeks in case there was a complaint, Ciba revised the method and brought in the listener clubs since some were doing this job for BBC.

This ‘voting’ by the end-users – listeners or viewers – was a standard practice to ascertain the popularity of films in the 1950s when the Filmfare Awards were launched. Indeed, the process for selecting the winners – Best Film, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Director – would start with the entries being made available for public voting. Typically this happened through forms printed in the magazine that was fortnightly and, later, monthly. Based on the number of votes polled, a shortlist of top entries was then curated. So, even if a jury decided the final outcome, people who disagreed would say, “Oh! Yeh to khareed liya hai, this award has been purchased!”

Ameen Sayani at work (Pic: Internet)

So what was the actual process Binaca Geetmala adopted for the countdown? This is what I’m told:

“For the countdown, Binaca Geetmala relied on a combination of record sales figures and input from dedicated listener clubs. The process started in a simple way and evolved over time to ensure accuracy and prevent manipulation…”

Evolution of the Countdown Method

o Record Sales: A major component was the number of records sold across approximately 40 identified record stores throughout India. Representatives from the sponsoring company, Ciba, would collect these weekly sales reports.

o Listener Input: Popularity was also gauged through listener feedback, initially via postcards. This was later formalized through a network of Radio Shrota-sanghs or listener clubs across the country, who would send in their weekly top song lists (Shrota sanghon ki rai). At the peak of the programme’s popularity, Geetmala had about 400 radio clubs. This helped to capture listener interest for songs that might have been sold out in stores. Jhumri Talaiya, a small mining town in what was then Bihar (now Jharkhand), became legendary as listeners from the town sent hundreds of postcards and letters each month to Geetmala.

The weekly results were then compiled into the final list that Ameen Sayani would present in his unique and captivating style, counting down the songs using the word paidaan, steps. The annual year-end lists were determined by the points each song accumulated throughout the year. (Information gathered from Rajil Sayani and from the Net)

Binaca Geet Mala Silver Jubilee EMI records Vol 1 (1953-64) and Vol. 2 (1965-77)

In the 1980s Binaca – the brand name of a toothpaste – metamorphosed into Cibaca, “because Ciba Geigy sold the brand to Reckitt & Colman and later to Dabur,” informs Rajil. One learns that at the outset of the present millennium – from 2000 to 2003 – it had even transformed into Colgate Cibaca Geetmala! But for most listeners like me it continued to be ‘Binaca Geetmala.’

Ameen Sayani recording a spot

(Rare photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

Little did we know about ‘sponsorship’ in those days. So for us the jingle Sirf ek Saridon was more about the Saathis than about sardard se aaram. This hit program featuring interviews with legends of the screen world played on All India Radio’s Vividh Bharati channel. Little did we know that this source of entertainment was a commercial success story too, being the first sponsored programme on the national broadcaster. And along the way it became a collective cultural experience.

This was a time when newspapers did not give much column space to cinema or film stars. The only concession made to new releases was the Reviews of the Week, ensured perhaps to draw the ads every weekend. Stardust was also a far cry in the golden age of Trade Guide, so the only peep into the personal stories of icons who livened our dreams was ‘Saridon Ke Saathi’: through anecdotes it took us away from the footlights, into the struggles, the joys, the rewards of people who were jaane pehchaney log, even aponjan to me, growing up in 2 Pushpa Colony that was home to art directors, cinematographers, writers, singers and assistant directors.

Imagine my excitement when Baba was invited to speak about three of his closest companions in his journey through sight and sound! But Baba refused to discuss any ‘list of names’ – so I had to hear about his companions on our Murphy Baby!

I remember that after the recording Baba had come home with a photo album that he kept with him till the last day of his life. We were delighted as it had a concealed musical contraption that would play every time we turned the pages of the album. At some point in time the contraption stopped working but the music played on in Baba’s ears, I’m certain, as the pages of the album filled up with more peerless saathis – like, Ameen Sayani.

100 songs with commentary from Ameen Sayani’s Geetmala (Vol-1) Ameen Sayani

***

At school and play all through each day – that energy, for boys and girls… it’s Bournvita! If Binaca Geetmala trained our ears in music, Bournvita Quiz Contest opened our minds. At the risk of sounding like a braggart, I must say that I was always the first with questions and, almost always, ready with answers. This could be ascribed to my being, always and without fail, surrounded with books, books and more books. These books were in English and Bengali and Hindi and – some – in Sanskrit too. They ranged from literary classics to bestsellers, travelogues to philosophy. There were tomes on cinema, drama, art, music to mythology, epics, and world history. Despite this, I did not grow up to be a Quizzer; instead, I became a Debater – “tarkobagish,” as Maa would say, dismissing my argumentative skill.

However when it was my turn to mother Devottam, I became a Quiz Master. I could draft complete Quiz sessions for the pre-teens and teenagers, complete with visual, aural and oral questions. Where did this confidence come from? Did I fancy that my General Knowledge, as much as my English, was as perfect as Hamid Sayani’s? Preposterous as that may sound, I don’t think I was a bad quiz master. Because, my son grew up Quizzing. Through school and college. In neighbourhood festivities. On television. In Mindsport. Facing the formidable Siddharth Basu in the Quiz Master’s chair. Why, he even captained the National Law School of India University team that emerged semi-finalist in University Challenge India 2004!

Ameen Sayani (L) and Hamid Sayani (R) with their mother

(Photo courtesy Ameen Sayani Archives)

Crux of the story? When Hamid Sayani passed away in 1975, it was Ameen Sayani who stepped into his L-sized shoes. And he carried off that task with equal flamboyance! For a year he did the opening and closing with Hamid’s quizzing. Then a substitute was introduced – only to be replaced by Ameen Sayani. He continued to host it for eight years – cementing its place in Indian pop culture until television came in…

Derek O’Brien turned it into a phenomenon on the idiot box of the 1990s.

More Must Read in Silhouette

‘My heart swells with pride when I see their work’: Nabendu Ghosh in conversation with Ameen Sayani

In Search of Forgotten Melodies: Vignettes From Bengal’s Musical History

Calcutta Sonata – The City’s Sustained Love Affair with the Piano

Harmonium — A Symbol of Interconnected Lives

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.

Very nice, comprehensive article, thanks for sharing!

This write-up on Ameen Sayani is not just a tribute; it reads like a return to a shared past shaped by memory, sound and quiet emotion. Ratnottama Sengupta blends personal recollection with careful historical detail and in doing so let’s radio emerge not merely as a medium but as a companion and a guide. What makes the piece touch a chord is how closely it resembles our own routines of that time. Homework had to be finished, dinner eaten early and the radio tuned well in advance, sometimes after a small struggle, so that nothing from the opening namaskar was missed.

Once the programme began, the house simply fell silent.

The jingles still come back without effort. “Mummy kehti hai I love you, Daddy kehte hain I love you…” and suddenly one is back in those evenings when even advertisements felt playful and welcome. Ameen Sayani’s cheerful “Aadha toothpaste” advice was another such moment, remembered as much for the smile it brought as for its cleverness, even if the tube never really lasted as long as hoped.

The reading of letters, names like Jhumri Talaiya and the slow paaydaan of the countdown created a sense of belonging that listeners shared across homes and towns.

These small memories explain why “Binaca Geetmala” was never just a music programme. It shaped habits, sharpened ears, and quietly refined taste and language. By capturing this collective experience with warmth and ease, the article places Ameen Sayani exactly where he belongs, not on a paaydaan of reverence, but seated comfortably in the living rooms of our memory.

I’m delighted to read this comment. I have shared it on FB.

Thanks so much!

Pingback: Carnival of Blogs on Golden Era of Hindi Film Music – Volume XIV – January 2026 Edition – The world is too small? or Is it?