A polymath shaped by revolution, folk memory and Western symphonies, Salil Chowdhury redefined Bengali music. Soumyadeep Chakrabarti revisits his extraordinary journey, from IPTA anthems to iconic collaborations, uncovering the modern musical ideas and progressive social consciousness that made ‘Salil Sangeet’ a genre of its own.

Salil Chowdhury immersed in a book (Pic: Facebook)

Rewinding Salil Chowdhury’s Bengali songs each time is not only a musical delight but also a fascinating journey down both the historical and melodious lanes, starting from the pre-independence era of India’s freedom struggle.

Thus, whenever his signature Bangla songs, especially the mass-awakening ones, spring up in mind, it’s not Salil Chowdhury’s music and lyrics alone; it becomes Salil Darshan, or a broader philosophy of life, if I may humbly put it so.

As music composer Naushad had said, Salil Chowdhury was a communist by ideology and had stuck to its principles. He never compromised with his musical approach. The many-in-one musical vision, where the music of River Indus flowed to join the music of River Rhine, the confluence may be named as Salil Sagar. They created tunes, and he created symphonies. Thus, Salilda is a phase of evolution not only for Indian music but for world music as a whole. Only conscious listeners of his Bengali songs, in particular, may define his works as Salil Sangeet, much like Rabindra Sangeet or Nazrul Geeti.

Lataji in one of her interviews had described her favourite composer to be a blend of Amir Khusrau, Rabindanath Tagore and Kahlil Gibran, and that delivering his songs every time was her greatest challenge even after working with 100-odd composers. And that says everything. Salilda was not just another composer in Indian music, but a Renaissance man shaped by the spirit and depth of the Bengali Renaissance itself.

Salilda’s sense of creativity in literature and music emerged very early and dates back to his childhood days in the sylvan tea estates of Assam. His father, Shri Gyanendranath Chowdhury, was posted there as the doctor for the plantation workers. Back then, the tea gardens were a hub for workers from different parts of India, who often performed their own characteristic folk music after a hard day’s work. Salilda’s sense of folk music and love for nature emerged from the music of tea garden labourers. Besides, his patriotic instinct was inspired by his father, a staunch supporter of the Indian freedom struggle and the Non-Cooperation Movement led by Gandhiji.

Gyanendranath Chowdhury was a connoisseur of Western classical music. The symphonies of Mozart and Beethoven, which he later introduced and blended with folk and classical music during his illustrious career, had run deep in his heart since those tea garden days. His love for theatre also originated with his father, who dared to organise the subjugated workers under British colonial rule to stage plays on the tea gardens’ campuses. Also, his love for literature and other forms of Bangla songs grew under his mother, who was an avid reader of Bangla books and a passionate listener of Bangla songs.

A young Salil Chowdhury

Following his migration to Kolkata for high school and college, Salilda was fortunate to be nurtured by his elder cousin, Shri Nikhil Chowdhury, who was an accomplished musician, playing orchestra music in the background of silent movies back then. It is from here that Salilda learnt to play musical instruments (the flute being his favourite) and accompanied his cousin’s orchestra, Milan Parishad.

Salilda then moved to his maternal uncle’s place in Subhasgram, South 24 Parganas, rural Bengal, while pursuing his college degree at Bangabasi College, Kolkata. The ambience of rural Bengal had a deep impact on Salilda’s creative genius. It is from here that he became deeply involved in the peasant movements of stormy Bengal under British imperialism. His first Bangla song was composed during this time in support of the farmers’ agitation against floods and the subsequent destruction of their crops, their hard labour wasted. Besides, his musical concept evolved while watching rural operas and listening to the rural music of the peasant land.

His introduction to the Communist Party occurred in college, and his natural patriotic instinct took a clear socio-political form. By this time, the radical theatre movement IPTA also took shape, and Salilda became an activist of it in 1944, penning and composing Bangla songs in support of the radical movement, which included peers like Balraj Sahni, Shambhu Mitra, Debabrata Biswas, Hemanga Biswas, and Suchitra Mitra, to name a few.

In Salilda’s words, the National Conferences of the Indian People’s Theatre Association were his university of music learning, as he got introduced to the mass songs nationwide. By the time he left for Mumbai, Salilda was an accomplished lyricist, arranger, and composer whose vision was to create genres crossing all boundaries. No wonder his popular song for Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin in the form of Hariyali sawan dhol bajata aaya was set to the tune of one of his earlier IPTA songs composed to foster the peasant movement.

Salil Chowdhury was a dedicated student of creative arts, not for entertainment alone. His sense of music was different from that of his peers. He wrote poetry, plays, and short stories based on the socio-political content of his stormy times, and his compositions, too, were a deconstruction and reconstruction of conventional musical forms such as Rabindra Sangeet, Indian classical music, and Kirtan genres. He was a step ahead of the rest in creating symphonies and blending folk music from different corners of the world.

His Bollywood chapter was significant for his collaboration with the noted Goan arranger Sebastian D’Souza, from whom he gained newer insights for his subsequent compositions. Salilda was born and shaped in stormy times and further evolved in his journeys in commercial Bollywood music.

A comprehensive understanding of his Bangla songs can only be reached if one gets to understand the entire Salilscape.

Having said this, his Bangla songs can be classified into two groups: the pre-Bollywood chapter or songs of his stormy times in association with mass movements, and basic or film songs composed after he migrated to the Hindi film industry.

With the harmonium

Written and composed in 1949, just two years after Indian independence, and titled as Ghum Bhangar Gaan (Song of Awakening), Salilda gives a clarion call for comprehensive freedom in all respects. A verse of illusion and disillusionment, Salilda composed the song on a slow rhythm to start with, painting the illusion of freedom with metaphoric expressions depicting that the struggle for true independence is not over yet, and one needs to march miles ahead to achieve the same, just like rowing a boat ahead from a desolate island to the point of the lagoon.

The meter changes abruptly, the rhythm becomes fast with the lines Ahobhan shono ahobhan. Salilda uses his signature choral scores, in fact overlapping choruses, to evoke deep patriotic instincts and match up with the articulate lines Jatra shuru uuchhol durbar bege totinil (the independence rally has begun and marches ahead like a river in full flow). A timeless masterpiece that is still being played in many mass gatherings, illustrating the eternity of his creative genius.

Here is to the song and Salilda’s narration of its socio political context.

O Alor Pothojatri (Non-film, 1949) Montoo Ghosh / Calcutta Youth Choir, Sabita Chowdhury

Written and composed in 1951, the song is set in the post-Second World War period, following which some colonial countries, including India, were liberated. However, the world was divided over the agenda of war and peace, and several movements in favour of peace emerged globally. Salilda’s creative genius was triggered to compose this brilliant song in support of the international peace movement, with his signature ups and downs of tunes and rhythms matching his vibrant lyrics.

The eternally inspiring lines,

Jokhon proshno othe juddho ki shanti,

Amader beche nite hoyena ko bhranti,

Amra jabab di shanti shanti shanti

(in the choice between war and peace we are united, despite the difference in our socio political outlook) strongly demonstrate his stance for global peace and harmony.

A masterpiece composition that is still sung and played today by several choirs in Bengal. Onward to the song with Salilda’s oration of its backdrop scenario.

Amader nanan motey (Non-film, 1951) Montoo Ghosh / Calcutta Youth Choir, Sabita Chowdhury

Yet another marvellous testimony of the torrid times during the colonial rule in support of The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946. A powerful patriotic song to stir up the feelings of lakhs of Indian people rising against British rule in the form of a strike observed on 29 July 1946. The portion Aaj hartal aaj chaka bandh, with its powerful delivery, is bound to give goosebumps and evoke deep patriotic feelings within one’s heart. One of his most popular mass songs for sure because of its powerful lyrics and amazing composition.

A song as powerful as Tagore’s terrific patriotic composition Baandh bhenge dao. No wonder Salilda considered Gurudev Tagore the founder-father of mass songs in India and carried forward his rich legacy.

Dheu uthchhe kara tootchhe (Non-film, 1946) Montoo Ghosh / Calcutta Youth Choir, Sabita Chowdhury

At the first International Peace Conference, held in Paris in 1949, the legendary artist Picasso’s painting ‘Peace Dove’ stole the hearts of all and was acclaimed as the symbol of world peace. In this background, the then poet of Bengal penned a beautiful verse Ujjal ek jhank payera surjer ujjalo roudre chancholo pakhnay uurche, describing a flock of pigeons flying in the sky in bright sunlight, depicting world peace so very metaphorically.

Sandhya Mukherjee and Salil Chowdhury

These captivating lines inspired Salilda, who went on to compose one of his most popular Bangla basic songs, with the noted singer Sandhya Mukherjee rendering it in her enchanting voice. The song starts with a beautiful prelude which sets the serene tune of peace instantly, and then the signature orchestration of Salilda takes over to paint an expansive canvas, complementing the lines

Tumi nei

ami nei

keu nei keu nei

ore sudhu ek jhank payera

(you and me have no individual entity and we are an integral part of peace spreading out in the vast sky in the form of white doves).

A timeless masterpiece that any music lover would like to listen to a thousand times and over.

Ujjal ek jhank payra (Non-film) Bimal Chandra Ghosh / Sandhya Mukherjee

In a tribute to his beloved Hemanta Da after his passing in 1989, Salilda fondly recalled the day he first met the rising singer through a friend from the Communist Party back in 1948 or 1949. By that time, Salilda was already a well-known figure in the IPTA circuit. His powerful mass songs, stirring public consciousness and demanding social rights for the subjugated classes, had brought him under the scrutiny of the police. The Government of India had banned the Communist Party, and many of its activists had been imprisoned.

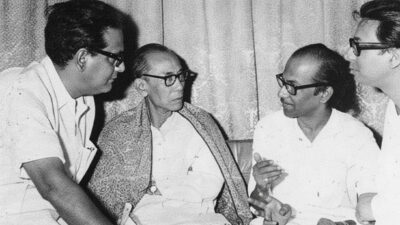

Bengal’s Music Makers: Hemant Kumar, SD Burman, Salil Chowdhury and RD Burman

Against this turbulent backdrop, Salilda visited Hemanta Mukherjee, then affectionately nicknamed “Junior Pankaj Mallik”, at his residence, hoping to have some of his mass songs recorded by the popular singer. However, Hemanta politely declined, explaining that since those compositions were written for choral performance, they did not align with his vocal style.

When Salilda, while leaving the house, told him of a song Gaanyer Bodhu (village bride), which was yet to be completed, Hemanta called him back. Salilda gave a demonstration and Hemanta asked him to complete the song at the earliest. In Salilda’s words, Hemanta Da always had a passion for new and off-the-track creations that made him such a great singer and composer both.

Within a few days following this historical meeting of the two rising lyricist, composer and singer, Salilda, pursued by the police, had to move away to the remote villages of the Sunderbans Delta in South 24 Parganas of Bengal.

Hemanta Mukherjee took all the pains by himself to record the song Gaanyer Bodhu with his own musical arrangements, which instantly became a super-duper hit. Never before in Bengal had one heard such a narrative ballad, with its amazing twists and turns. The song transported both Salil and Hemanta to a different plateau. Hemanta Mukherjee established himself as a classy singer different from the hitherto Pankaj Mallik shadow, and Salil Chowdhury stretched himself ahead from his domain of mass songs.

Thus began a golden chapter in the history of Bengali modern songs, perhaps the most phenomenal lyrical and musical event since the Tagorean era. This duo worked wonders to come up with newer forms of basic songs, each being different from the other in context and style. This was a renaissance in the field of Bengali song, preparing the ground for Salil Sangeet to mature and bloom, captivating the hearts of millions of music lovers then and now.

During the Second World War, the agricultural economy of a blooming Bengal was gradually crippled by the British government’s strategic move, which created a food grain crisis in rural Bengal, as Bengal was then the centre of the freedom struggle. While black marketeers prospered, lakhs of poor peasants from villages flooded the streets of Kolkata begging for food. Lakhs of them died, and streets were littered with dead bodies. Such was the intensity of the infamous Bengal famine.

Salilda had witnessed these events during his visits to rural areas to provide relief in the form of food and medicines. This stirred him to pen down one of his most amazing lyrics and compositions.

A ballad that starts with the description of a happy farmer’s bride (Gaanyer Bodhu), who lived merrily, only to have her happiness cut short by the outbreak of famine, metaphorically described as Dakini Jogini (ghosts and witches) in the song. The sharp shift in rhythm, with a sad ending, set to a tune inspired by Bihu folk music, is the hallmark of this composition. A game changer in the history of Bangla basic songs for sure.

Gaanyer bodhu (Non-film, 1949) Salil Chowdhury / Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Sukanta Bhattacharya

A deeply heart-touching poem of Salilda’s close friend Sukanta Bhattacharya, who sadly left for his eternal abode at the tender age of 21 years, describing the breathtaking night-long journey of a postal peon (Runner) through dense and wild forests to deliver letters and money orders to the post office by early morning.

The colonial life of the subjugated masses of British India, being painted so lucidly in words, prompted Salilda to compose the song for Hemanta Mukherjee in 1951. The most amazing form of musical expression is the ups and downs of rhythm, and one can easily visualise Runner’s risky journeys through forests invaded by dacoits and wild beasts. Raat nirjon pathe koto bhoy tobuo runner chhote depicts subjugation in its worst form, brought alive by Salilda’s melodic magic and Hemanta Mukherjee’s golden voice.

The song ends on a brilliant note of sunrise and hope, where Runner is described as a messenger of an exploitation-free new world. Only the combined genius of Salil Chowdhury and Hemanta Mukherjee could transform this terrific verse to such amazing melodic heights.

Runner (Non-film, 1951) Salil Chowdhury / Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

A beautiful composition penned and composed in 1952, painting the journeys of struggling fishermen in earning their livelihood. Dark clouds hover above, the rivers turn turbulent, but the poor fishermen have no other choice but to proceed ahead, risking their lives day in and day out.

One can visualise the entire scene and feel the sound of rowing fishing boats as the song progresses, ending with a note of hope that these subjugated people look forward to in the days to come. A very serene composition, with subtle background music, brought to life by the magical voice of Hemanta Mukherjee.

Nauka baoaar gaan (Non-film 1951) Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Rai Bahadur (1961)

A gem of a song, penned and composed for the Bengali movie Rai Bahadur back in the 1960s, with very subtle background music. The use of the flute and sitar is just fascinating, and one can visualise the rolling sea waves while listening to the interludes. Also, the depth of the lyrics is heart-touching. Salilda’s love for life is beautifully painted by the words E amar ononto prem muhurter majhe dhora thak na.

A composition that crosses the boundaries of a romantic song and transcends to a deeper level, the love for humanity, so characteristic of Salilda. A wonderful Hindi version of the same song was composed by Salilda for the film Honeymoon in 1960, with Mukesh’s voice being complemented by choral scores of Lata Mangeshkar.

Jay din emni jodi jaye jaak na (Rai Bahadur, 1961) Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Mere khwabon mein khayalon mein chhupe (Honey Moon, 1960) Shailendra / Lata Mangeshkar, Mukesh

The musical camaraderie of Salil and Hemanta that revolutionised the approach to Bangla basic songs reached a peak before both moved to Bombay in the early 1950s to explore new horizons in Hindi film music. As a result, the consistency of the magical numbers from the legendary duo gradually began to fade away since their dream run began in 1949.

However, the duo made a great comeback in 1969 (almost 8 years after) with two beautiful songs that remain very popular today and are sung by younger artists in various musical programmes and contests.

A very popular number, the tune of which was again utilised by Salilda for the film Anand with lyrics penned by Gulzar in the form of Kahin Door Jab Din Dhal Jaye.

The Bangla verse is indeed thought-provoking, and it seems that Salilda’s ending lines, Ami sudhu tusharito gotihin dhara (that I am a frozen stream amidst all the dynamics around me), are in remembrance of his IPTA days that continue to haunt him despite his commercial success in Bollywood music.

Amai proshno kore neel dhrubatara (Non-film 1969) Salil Chowdhury/ Hemanta Mukherjee

Kahin door jab din dhal jaaye (Anand 1971) Yogesh / Mukesh

An amazing composition with vibrant background scores. The marching orchestra is a signature Salil piece, and one can immediately recognise it as Salil Chowdhury’s composition from the prelude. The musical progression is fascinating, and so are the lyrics. The description of a monsoon night with clouds hovering around the moon is simply mystical.

Once again, Salilda’s love for the zest of life is evident in the lines Shuni jibon joyer geet gatri, and the song immediately transcends itself from a typical romantic song to the victory song of human life.

Shono kono ekdin (Non-film 1969) Salil Chowdhury / Hemanta Mukherjee

Following Salilda’s new chapter in Bombay film music starting with the film Do Bigha Zameen in 1953, Bengali basic songs soon experienced another phase of evolution in the form of the Lata Salil magical duo. Again, a new chapter began after the Hemanta-Salil one.

During the period when there was a gap in Hemanta-Salil melodic outputs, Lata-Salil filled up the space with some mesmerising songs that continue to enthrall music lovers back then and generations to follow thereafter.

Lata Mangeshkar and Salil Chowdhury

(Pic: lataonline.com)

Penned and composed in 1959, this is arguably the most popular song of the duo. Lata’s nightingale tone and Salilda’s signature tune, set to Raga Khamaj with the beautiful application of sitar strings in the background, elevate the song to ethereal heights. The same tune, with a different background and a more prominent sitar, was used by Salilda in the Hindi movie Parakh in 1960 to evoke a romantic monsoon mood. Both versions have a Salilda-woven beautiful sanchari that makes them so special on this day.

Na jeyo na (Non-film 1969) Salil Chowdhury / Lata Mangeshkar

O sajana barkha bahar aayi (Parakh, 1960) Shailendra / Lata Mangeshkar

Yet another of the most popular songs of the duo. Lata’s nightingale tone builds up the melancholic mood of the entire song based on Raga Malgunji.

E nodir dui kinare dui toroni

Jotoi nabai nongor bandha kaache jete tai pari ni

(the two boats anchored at two opposite banks of the river cannot meet in spite of endless rowing)

Perhaps it is the lament of the lyricist when he realises that he can’t row back to his wandering youthful days. Thus, once again, so characteristic of Salilda, his song spreads beyond a romantic number and expresses the bitterness of his life in a broader perspective.

The Bengali number was penned and composed by Salilda in 1969 and has a very popular Hindi version for Anand rendered by the same songstress. Both forms are decorated with beautiful sancharis and very subtle background scores. The tune got a new version again in the Tamil film Azhiyatha Kolangal with SP Balasubrahmanyam’s popular Naan ennum.

Na mono laage na (Non-film 1969) Salil Chowdhury / Lata Mangeshkar

Naa jiya lage naa (Anand, 1971) Yogesh / Lata Mangeshkar

Naan ennum (Azhiyatha Kolangal, 1979) Gangai Amaren / SP Balasubrahmanyam (Tamil)

A song of hope amidst anguish emerging out of personal bitterness in life, yet embracing the joyous side of it with his faith in humanity as the shining beacon. Salilda spins a musical web with vibrant preludes and interludes that light up melodic sparklers to complement the lines, O Butterfly, open your wings wide to light up colourful sparklers in the dark corners of my heart.

O projaapoti, projaapoti paakhna melo (Non-film 1971) Salil Chowdhury / Lata Mangeshkar

A masterpiece penned and composed in 1971, with two beautiful Malayalam adaptations in the form of O neelanadhi neelanadhi by Unni Menon and KS Chitra, respectively.

O neelanadhi neelanadhi (Cover version, 1991) ONV Kurup / Unni Menon (Male Version), KS Chithra (Female Version) (Malayalam)

A gem of a verse and composition of 1961, tailor-made for Lataji’s nightingale tone. Salilda’s love for Western symphonies is evident in the song. Mozart’s symphonies come into play in the prelude and interlude while the basic tune seems to be shaded with the Hindustani Raga Kedar.

Salilda’s concept of creating genres that would cross boundaries is so aptly demonstrated in this song as well as in its Hindi form Aansoo samajke kyun mujhe by Talat Mahmood in the film Chhaya of 1961.

Ki je kori, durey jetey hoi taai (Non-film, 1961) Salil Chowdhury / Lata Mangeshkar

Aansoo samajke kyun mujhe (Chhaya, 1961) Rajinder Krishan / Talat Mahmood

Salilda’s life vision can be very well understood from one of his interviews published in The Telegraph on 21 November 1993.

Thus, it is understandable that a successful career in the glamorous Bollywood film industry could not derail his basic principles acquired through his struggle experiences.

So he writes in 1977 for Lata to render the song Aaj noi gungun gunjan premer.

No more murmurs of love, songs of the moon, flower or the moonlight.

Release your embrace my love, as the world calls you.

Go and see whose hut is lightless, whose children are hungry.

A song of humanity, compassion, gender equality and social bonding, the spark of love for life burns bright in his heart. It transports one to the IPTA days of Salilda when he composed such songs of awakening in plentiful.

The Bengali song has a subtle background music, whereas its Malayalam and Kannada versions, sung by S. Janaki and P. Susheela, are enriched with vibrant background scores, the signature orchestration of the maverick Salilda.

Aaj noy gun gun gunjan premer (Non-film, 1977) Salil Chowdhury/ Lata Mangeshkar

Rappadi paadunna (Vishukkani , 1977) Sreekumaran Thampi / P. Susheela (Malayalam)

Sanje tangaali myjokalu (Kokila, 1977) Udayshankar / S Janaki (Kannada)

In the process of revolutionising the approach of Bangla songs with Hemanta Mukherjee and Lata Mangeshkar in the lead role, Salilda penned and composed some of his very popular Bengali numbers for Sabita Chowdhury. The many-in-one concept of Salilda was notable in these songs, ranging from folk music, choir music, chorus to Indian classical genres.

Sabita Chowdhury went on to sing the maximum number of songs composed by Salilda, not only in Bengali but also in Malayalam, Tamil, Assamese and Oriya. The Salil Sabita duo will definitely be remembered as a significant chapter in the history of Bengali modern songs.

A pathbreaking Bengali song penned and composed in 1958 with melodies and counter melodies and overlapping choral scores, a must-sing number for any choir troupe in Bengal even today. It is worth mentioning that this song was rendered by Calcutta Choir once again to mark the birth centenary of Salilda at Kalamandir Auditorium, Kolkata, on 19 November 2025. Salilda’s love for nature and zest for life is beautifully expressed in the lyrics of the song. Salilsangeet at its harmonious best.

Surero ei jhar jhar jhar jharnaa (Non-film, 1958) Salil Chowdhury / Sabita Chowdhury

An amazing composition with vibrant background scores and visual impact. Salilda paints a beautiful naturescape with heart-touching lyrics and adds melodic hues with his signature orchestration. His desires and wishes seem to be unleashed like multicoloured butterflies in the air. His playful, childlike heart is in chase of those butterflies of myriad colours.

Salilda’s imagination, quest and chase for newer and newer horizons of creative arts is depicted beautifully through his expressions. The rhythmic orchestra adds so many hues to the lyrics.

Projaapoti projapoti (Non-film, 1972) Salil Chowdhury / Sabita Chowdhury

The Hindi adaptation is the highly popular song Janeman Janeman rendered by K. J. Yesudas and Asha Bhosle for the movie Chhoti Si Baat in 1975. A Telugu adaptation of the song was used in the 1974 movie Chairman Chalmayya, starring Salilda. Salilda’s concept of creating genres that cross all boundaries is evident again while listening to the same tune with different background music for each.

Jaaneman jaaneman tere do nayan (Chhoti Si Baat, 1960) Yogesh / Asha Bhosle and Yesudas

A very serene song set to the tune of church hymns, penned and composed for the Bengali movie Sister back in 1977. Salilda’s long association with Malayalam film industry, through which he had picked up the church hymns of Kerala, is understandable on listening to this Bengali song. His innovative mind to experiment with new genres and his vision for a peaceful world is evident again from the melody and lyrics of the song.

Biswapita tumi hey Prabhu (Sister, 1977) Salil Chowdhury / Sabita Chowdhury

Asha Bhosle and Antara Chowdhury sang the Hindi version of the song for the Hindi movie Minoo released in 1977. The Bengali version was sung by Antara Chowdhury and his students of Surodhwani in remembrance of Salilda on the occasion of his birth centenary at Kalamandir on 19 November 2025, which goes on to demonstrate the eternity of this sublime Salilsangeet.

Dheere dheere haule se (Minoo, 1977) Yogesh / Asha Bhosle and Antara Chowdhury

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.

Soumyadeep Chakrabarti’s article on Salil Chowdhury is a rare example of sensitive, well-researched, and deeply empathetic music writing. What makes the piece truly special is that it does not merely catalogue Salil da’s achievements; it traces the inner journey of the man—how environment, ideology, and lived experience shaped one of the most original musical minds of Indian cinema.In an age of hurried, superficial writing, publishing a nuanced and reflective piece like this is itself an editorial statement. Congratulations to Antara and SILHOUETTE’s commitment for preserving the legacy of artists who shaped our collective aesthetic consciousness.

Thanks a bunch Ajay Kanagat Sir for your words of appreciation. Just a humble effort of mine to paint the Renaissance Man on the socio political canvas of his times. Worthwhile to mention here that another legendary personality of Bengal Shri Soumitra Chatterji had described Salilda as the best lyricist and composer to have been born after Gurudev Rabindra Nath Tagore

Very well and carefully written. It gives wonderful insights into Salil da’s Bengali music that a non-Bengali like me may have missed.

Once Salil da’s son Sanjoy Chowdhury shared in a show that the best advice his father gave him was not to use any instrument while composing a tune because if you compose with harmonium or any other instrument, his creativity will get limited by the limitation of that instrument. Instead he advised Sanjoy to compose tune in his mind and then polish it with musical instrument.

What an incredible insight. Fortunately I was in the audience in that show and thats why I remember it.

Thanks so much for your patient reading and words of appreciation Kunal Desai Sir

Salil chowdhury was an institution in himself!

Well documented work on the life and works of the maestro. Particularly, the political and historical background of his immortal compositions, establishes the author’s well documented research on salil chowdhury. There are many unknown episodes of his life and works unveiled through this document.

Thanks Debasish for your wonderful comments

Immensely elated indeed !

Amazing description of Salil sagar.

You have got a big canvas, throw all the paint you can on it .

Waiting for more.

Thanks a lot Sudip !

Would definitely come up with more of Salil Hues,hopefully soon

Vsevolod Pudovkin, a Soviet film director, screenwriter and actor who developed influential theories of montage once said, “Salil Chowdhury is the best elevator of Indian Folk Music.” However, this was a little appreciation for someone who has been much larger than life.

Salil Chowdhury, as author Soumyadeep has correctly mentioned, was a polymath. He was not just a lyricist or composer; he was a poet, a story-writer, a novelist, a teacher and, above all, a social activist.

Author Soumyadeep’s coinage of words “Salil-Sangeet” is perhaps the best to describe Salil Chowdury’s musical triumph in the post Rabindranath Tagore era. His compositions, though complex and euphonious, could touch the hearts of millions. Therefore, Pandit Hariprasad Chowrasia said, “Even the lay man could tell his tunes apart.”

Besides, Salil Chowdhury was a great singer by himself. Any connoisseur can appreciate my view after listening “Na Mon Lage Na” in Salil Chowdhury’s exceptional voice. He performed beyond anybody’s reach in case of “Ei Roko, Prithibir Garita Thamao” (Hey Rocco, stop the car of the world).

Salil Chowdhury’s unmatched creations were the reflections of his deep philosophical commitment. While addressing a workshop on “Ganasangeet” during June, 1988 in Kolkata, Salil Chowdhury emphatically mentioned, “For those who are not directly involved in the mass movement, who have not been able to make the mass movement their own, mass music becomes a philosophical quagmire.”

That was Salil Chowdhury in short. I take this opportunity to extend my warmest thanks and greetings to the author Soumyadeep for such insightful article on legendary Salil Chowdhury whom, perhaps, we could explore yet in totality.

Thank you so much for your insightful words of appreciation Respected Dada. This really means a lot ! The term polymath was coined by the consulting editor Antara Nanda Mondol though

After a long time I am reading an article borne out of indepth research and knowledge. This is possible only by someone having deep love, admiration and adoration for someone. Such beautiful presentation is rare these days. The rare talent of such a great personality would be lost to the future generations if they are not chronicled. While talent is inborn and a gift of God, the rearing and upbringing makes a great artiste. No amount of teaching or training can create such a great composer. Every library of the world should possess this research piece.

Brilliant ! After listening carefully several times a live discourse of Kabir Suman on Phenomenal music director, song writer , lyricist , writer , poet and polymath Shri Salil Chowdhury Babu now we got another precious and significant draft penned by Mr.Soumyadeep in writing which is really enlightening and no doubt very interesting and inspiring contribution , he explored this topic in large canvas with socio – political lens and analysis on a Genius of India covering a themes and inputs like Salil Sangeet , Salil Darshan , Salilophile and Salil Scape etc with great passion , details , insight and care , I am still reading it carefully , and have to read multiple times more for better and in depth understanding, and would like more additional comments, and it should have further debate and discussions, this important draft on Salil babu needs to be published in course of time and is really valuable for up coming days discussion and analysis for young generation of India for more contemporary understanding and futuristic creative dialogue on life journey and inputs and genres and structures of music of Salil babu , many thanks to him and entire team of Silhouette magazine for this significant project and for such meaningful initiative , it ‘s so important for all of us to study much more how Shri Salil ji evolved by many layers of patterns of revolution, folkloric memories to Indian and Western symphonies and his amazing life journey with musical ideas and inputs and contexts and cultural impact with his ethnomusicology in terms of global performance studies and critical appreciation and cultural studies 🙏

Thanks so much Rudradeep for your patient reading and insightful comments. In fact I could catalogue only a few gems from his vast repertoire

Wish to come up with some of his awe inspiring mass songs sometimes later on.

Salil chowdhury will remain as the shining beacon for all who are in search of light amid darkness and hope amid despair

Thanks a lot for your wonderful comments Respected Kanhaya Bhai. It had started with my short essays for the music lovers group of ours and finally taken a concrete shape. Compliments from you really means a lot !

Pingback: Carnival of Blogs on Golden Era of Hindi Film Music – Volume XIII – Deceember 2025 Edition – The world is too small? or Is it?