& Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel  & Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel

Ek Din Pratidin offers a deep insight into the difference in treatment of and attitude towards men and women among the urban Indian middle-class tilted against women and towards men.

Chinu, a daughter who also happens to be the sole earning member of the family, fails to return home.

Mrinal Sen made Ek Din Pratidin in 1979, where, he developed an attitude of concern, compassion and anguish in his depiction of the Calcutta middle-class, bound by its narrow conventions and false moral values. Explaining this shift, Sen said, “I have continually been chased by my own times. As I am being shaped by my own time, so I go on reshaping time.” Changing with the political atmosphere of his immediate surroundings, Sen felt a need to retreat into himself and take stock. He felt the urge to analyse, as a Marxist, the new complacency that had entered the left political scenario. “I thought, now is the time to go into myself, to pull myself by the hair, to point my accusing finger at myself. It is not masochism. It is not self-flagellation; it is not self-pity either. What I used to do before was to locate my enemy outside me. Now I am trying to find my enemy within myself.”[1]

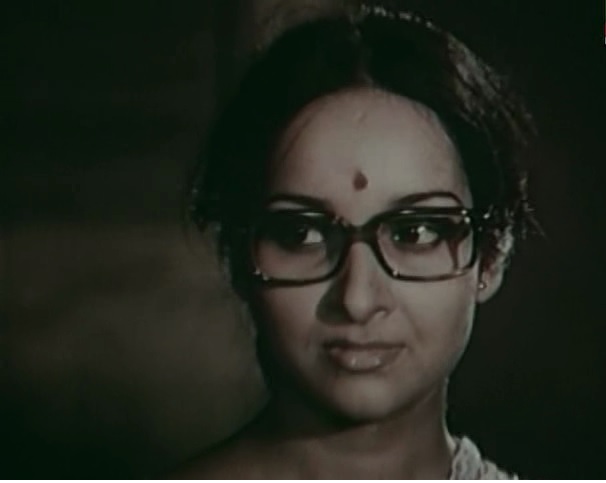

Ekdin Pratidin, based on a story by Amalendu Chakravarty entitled Abirata Chenamukh (Known faces, endlessly) describes the happenings of a day and night in a low-middle-class complex of flats where everyone knows everyone else and there is hardly any privacy. In one of these flats, Chinu, a daughter who also happens to be the sole earning member of the family, fails to return home. “It is somewhat in the manner of Henrik Ibsen, who begins with a big event that sparks off many things. I try to pick out small things from everyday happenings, from daily life, and try to give them shape, lead them to a point. The characters undergo a metamorphosis and enter into new relationships in the process, with an emergence of new values which is perhaps one of the hopes for survival,” says Sen.

With Ekdin Pratidin, Mrinal Sen entered his most creative phase.[2] He was done with experimentation. With Ekdin Pratidin, the bald statement of Parasuram (The Man with the Axe, 1978), gave way to allusive detail, an effortless creation of atmosphere and a multi-layered density. Both Oka Oorie Katha and Parasuram dealt with concepts half-way between the real and the imagined. In Ekdin Pratidin, the setting, the characters, the atmosphere, are Bengali middle-class. The awkward syntax and the restless camera of the former two films are more controlled. The style of Ekdin Pratidin says Sen, developed organically. It is not an intellectual imposition arising from a desire to innovate. There is unity of time and place and chronological progression.

The double standards are sharply defined in the contradiction that Chinu represents.

Ek Din Pratidin is one of Sen’s most poignant films and one that he produced himself. It has an unhurried pace that unfolds, layer by slow and detailed layer, the position of women in Indian society in general and of working women in middle-class families in particular. The unfolding of the story takes place in Calcutta with the dilapidated housing complex in which Chinu and her family live taking up a major slice of the space. The events begin and end within the span of a night, from the time Chinu fails to return from work, till the next morning when she finally comes home.

Sen places his characters within a definite architectural and situational setting that establishes their socio-economic status at once. The film opens on a shot of a rickshaw moving into the scene from one end of a narrow lane, as the camera pans to show a festoon of saris hung up to dry in the courtyard, with young boys playing football within the narrow lane. One of the boys, Poltu, is badly hurt at play and is taken to the local clinic for medicines and a dressing. Later, we learn that Poltu is Chinu’s youngest brother.

The double standards are sharply defined in the contradiction that Chinu represents. On the one hand, the family almost pushes her into the market place. On the other, it places severe restrictions on the hours she can be away from home. The family allows her to work because it brings them financial support. Yet, they do not hesitate to make value judgements on her absence, because of her absence. The family does not allow her to stay away from home because that is considered morally ‘improper’ by their self-defined and self-imposed norms of morality. The same family accepts that the adult son Topu, will not earn because he is ‘worthless.’ It does not bother about his geographical mobility, nor does it place any limits on his hours spent inside or outside the home. Poltu, who gets hurt while playing football on the street, is coddled and cared for but not reprimanded for playing on the streets though it compromises his safety.

Chinu is not only the main provider for the family, her work also allows her younger sister Minu to stop teaching at tutorials and concentrate on her studies.

This anachronism expresses itself in that if the protagonist had been a young man instead of a woman, the film could never have been made.[3] When Minu shrugs off Topu’s absence with ‘What use would he be?’ she hastens to add that he is never home before midnight anyway. Yet, when Chinu plays truant, the family and its neighbours are thrown into crisis.[4] Chinu is not only the main provider for the family, her work also allows her younger sister Minu to stop teaching at tutorials and concentrate on her studies. Probably, she is the next ‘goat’ to be sacrificed at the altar of family needs.

The strong presence of patriarchy comes across through newspaper headlines that flash on the screen after the scene at the hospital morgue when they discover that the dead body of the anonymous woman is not Chinu’s. It does not occur to anyone to question who the young woman is, how she came to be lying lifeless in the morgue, insensitive to the reality that she too, is someone’s daughter and sister and that her family might also be waiting for her at home. The newspaper headlines scream:

Woman’s Dead Body Floating in the Lake

Mutilated Body of Woman in a Trunk at Howrah Station

Pathetic Confession of a Call Girl in Court

A Survey of the Trade in Women’s Flesh[5]

The first two headlines are pointers to any city woman’s life being fraught with danger. The last two headlines carry suggestions of moral turpitude and social scandal. Chinu’s family displays both fear for her life and the fear of social stigma. However, it is the social stigma that concerns them more than fear for her life. This is borne out towards the end when Dwarik Babu gives notice to the family to leave, ostracising them only because their daughter did not come home the previous night! He does this without even knowing why she did not come home that night. Topu begins to attack him physically. But a friendly neighbour saves the fracas in the nick of time. Note that Dwarik Babu is not bothered about Topu coming home at midnight everyday because Topu is a man and his late coming is taken for granted.

The family greets her with explosive silence.

When Chinu comes back, no questions are asked. The family greets her with explosive silence. Her mother, who was the most vocal during her absence, rushes out to see her. As inquisitive neighbours throng the windows of their flats and the lights come up one by one, she tells her daughter, “come in now, and don’t make a laughing stock of yourself'” and goes into the room with her youngest daughter, leaving Chinu alone in the compound. Her younger brother tells his sister to step inside.[6] Inside the room, the mother sits quietly. Chinu’s father stands beside her, but does not speak.

No one asked Chinu questions because (a) they were relieved that she had finally come home; (b) they did not have the guts to antagonise the main bread earner of the family; (c) they were afraid to hear what she might have had to say and did not wish to hear it; (d) they did not wish to embarrass themselves in the presence of the neighbours not knowing what explanation she would give; and (e) they were trying to escape the reality of the situation by pretending that nothing was wrong and things were as ‘normal’ as “a day like any other” which is the right translation of the film’s title.

Ek Din Pratidin offers a deep insight into the difference in treatment of and attitude towards men and women among the urban Indian middle-class tilted against women and towards men. Earlier in the film, a voice-over establishes why a young woman in the family, normally ear-marked for marriage and motherhood, is forced to go out and work to keep the family fires burning.

Sen’s command over cinema as a social comment and cinema as an art form comes across well because in Ek Din Pratidin, he crafts and styles his statement by keeping the protagonist, Chinu, absent from the cinematographic space of the screen. In fact, her very absence makes the statement more intense and strong than it would have been with her presence. In Ek Din Pratidin, Sen proves that contrary to common understanding, not all working women are economically independent. In fact, her ‘independence’ is compromised by her financial responsibility towards her family. Whether this responsibility is acquired, circumstantial or coerced is beside the point. Whether she likes to take responsibility is never questioned. For women like Chinu, the responsibility is thrust on her, whether she likes it or not. It is part coercion and part circumstance. Once having accepted the burden, she is neatly placed in a no-exit situation.

End Notes

[1] Interviews with the author

[2] Vasudev, Aruna, The New Indian Cinema, Macmillan India Ltd, 1986, Page 30.

[3] John W. Hood, Chasing the Truth – The Films of Mrinal Sen, Seagull Books, Calcutta, 1993,p.74.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Datta, Nandita (tr.) ‘And Quiet Rolls the Dawn’, in Cinewave 1, January 1981, p.38.

[6] In an interview with Gautam Ghose, about the impact of Chinu not coming back home one night, Sen said: “When the family members do not know how to face reality, when they cannot endure reality, they fight among themselves, they tear one another into pieces.” Chitrabeekshan (Bengali)Cine Central’s magazine, special issue on Mrinal Sen, April-May, 1993, p.12.

Read more to read

Revisiting Swet Patharer Thala: Woman, Widowhood And Work

Deep Jele Jai: Representation Of The Physically And Mentally Challenged

Aranyer Din Ratri: Holding a Mirror to the 21st Century Generation

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

We are editorially independent, not funded, supported or influenced by investors or agencies. We try to keep our content easily readable in an undisturbed interface, not swamped by advertisements and pop-ups. Our mission is to provide a platform you can call your own creative outlet and everyone from renowned authors and critics to budding bloggers, artists, teen writers and kids love to build their own space here and share with the world.

When readers like you contribute, big or small, it goes directly into funding our initiative. Your support helps us to keep striving towards making our content better. And yes, we need to build on this year after year. Support LnC-Silhouette with a little amount – and it only takes a minute. Thank you

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.