A reading of Ritwik Ghatak and his alter ego Nilkantha in Jukti Takka Arr Gappo

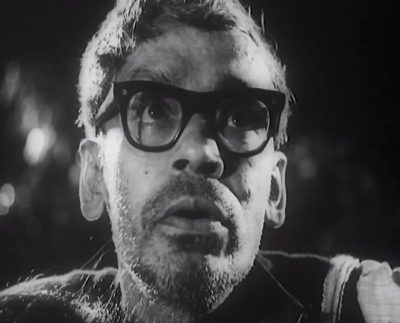

Ritwik Ghatak as Nilkantha Bagchi, a broken intellectual

Jukti Takka Arr Gappo was made at a time when Bengal was burning, India was burning. The Naxalite movement was being suppressed and quenched by brutal police force, the influx of refugees from across the border was creating unforeseen pressure on the economy of Bengal, corporate houses began shifting their headquarters westward, factories went on lockout, the youth of Bengal began facing severe unemployment. On the national front, there was corruption and lawlessness. Voices against Indira Gandhi’s regime were getting stronger. Situations were spinning out of control. Thus “Aami purchhi, brahmando purchhe, shob purchhe” (“I am burning, the world is burning, everything is burning”) became a refrain in the lips of protagonist Nilkantha Bagchi – an alter ego of Ritwik Ghatak, played by Ritwik himself.

In this film, we find Ghatak behind the camera and in front of it as well. In front of the camera, he projects himself as a ‘broken intellectual’ who is disillusioned, isolated, frustrated and hopelessly addicted to the bottle. Yet, he has not given up on life. He is hopeful that the Bengal of his dreams will be born one day. He is hopeful that his son will carry the legacy of his beliefs and he calls the Naxalite revolutionaries the cream of Bengal, even though they are misguided. Behind the camera, Ghatak masterfully wields a wide-angle lens to construct his narrative around the core theme that defines him as an auteur. But he is in no mood to tell a well-rounded narrative. He alienates, shocks and breaks the fourth wall from time to time. He also occasionally quotes from his earlier films and teases his spectators to join the dots, to connect, to recall. Watching Jukti Takka Arr Gappo (JTG) is more of an intellectual exercise than a drama that brings an emotional catharsis. The spectators are not drawn into the world of the diegesis. Ghatak makes it a point that they do not identify themselves or empathise with any of the characters, least of all with the unkempt, tottering drunkard protagonist Nilkantha Bagchi.

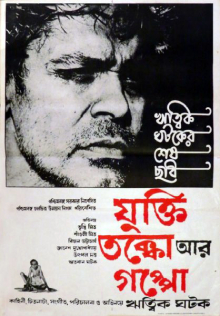

Jukti Takka Arr Gappo poster

Nilkantha Bagchi does not elicit pity, sympathy or empathy either from his spectators or from any other character in the film. The trajectory of his seemingly aimless journey is not marked with coincidence and melodrama, which have been a hallmark of Ghatak’s earlier films. Ghatak gives full agency to Nilkantha to decide his own fate, whether it is taking just ten rupees from the wad of money offered by his erstwhile friend or deciding to walk all the way to Purulia with his entourage. His co-travellers follow his footsteps without any question.

Interestingly, Ghatak gives some of the most quotable dialogues to Nilkantha. Dialogues like “Bhabo bhabo bhaba practice koro” (“Think, think, practise thinking”) have become synonymous with the filmmaker. Ghatak knew somewhere deep down that JTG would be his finale, his goodbye film. So, he comes out with all his disillusionment and dreams in this, layered with aural and visual signs that would require multiple viewings to decode.

The film begins with titles written by hand on a ‘dorma’ – a mat-like surface used for erecting walls of makeshift homes, to the accompaniment of tribal music. It raises an expectation that we are about to watch something very raw and makeshift, untouched by urban sophistication. However, to those who are familiar with Ritwik’s oeuvre, the ‘dorma’ surface would kindle memories of Meghe Dhaka Tara, a film about a refugee family from East Bengal. The ‘dorma’ walls were an important component of the mise-en-scène of their refugee home. In JTG, ‘dorma’ is the signifier of shelter or ‘ashray’, the ostensible goal of all the protagonists of the film.

The listless spectator who looks but does not see, sees but does not comprehend

The dancing trio try to arouse the listless spectator

Immediately after the title sequence, we see a haggard old man crouching underneath a makeshift shelter and gazing with tired eyes at something in front of him – almost looking into the camera. There is no pleasure or curiosity in his expression. If anything, there is only exasperation. What is he gazing at? The edit would have us believe that he is gazing at a spectacle of three dancers in body-hugging black dresses performing to the beat of an energetic ‘Chhau’ dance music. Their energetic dance is a contrast to the listless stoned appearance of their spectator. Whether the three dancers represent the Holy Trinity or the triumvirate Brahma Vishnu Maheshwar, they are unable to arouse their spectator from his stupor. They exit through the wings shaped like rocks and the diegesis begins to unfold.

Nilkantha’s wife Durga leaves him and she takes away his books and records so that he does not sell them off to buy the next bottle. The books will be the legacy through which their son Satya will know his father. In this scene of marital discord, we hear Beethoven’s 5th symphony playing in the background. Perhaps Beethoven’s 5th is among the records that Durga takes away. We would again hear the same music when the dying Nilkantha clasps Durga’s hand for the last time after falling to the bullet fired by the police. Perhaps the music is a reminder of the happy home they once had. This is the first time in his entire oeuvre that Ghatak uses Western classical music. Beethoven’s 5th serves as a refrain to underline a tender relation wrought with conflicting undertones.

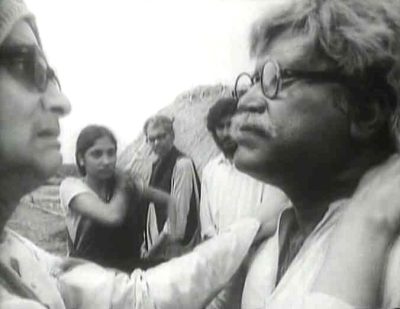

Aami toder dujonkei pagoler moton bhalobashi

Nilkantha takes to the road with his two companions – an urban unemployed youth and a refugee girl from Bangladesh whom Nilkantha calls the soul of Bengal. If one strand of JTG is about Nilkantha’s nemesis, the other strand is about the bickering between Nachiketa and Bangabala – the two faces of Bengal – East and West, urban and pastoral. Sitting on a bench to rest his tired legs, Nilkantha hugs his two young companions and says, “Ami toder dujonke pagoler moton bhalobashi” (I madly love both of you). The dialogue is reminiscent of Meghe Dhaka Tara where Neeta tells her brother Shankar that she madly loves her family. In JTG, this dialogue has deeper connotations. Nilkantha holds both faces of Bengal dear to his heart. He says, “Tora dujonei Bangladesher ekta ongsho. Je Bangladesh ekhono jonmayni” (Both of you are a part of Bengal – a Bengal that is yet to be born). This dialogue subtly suggests that he is not alluding to the new nation Bangladesh. He is dreaming of a utopian united Bengal.

Bangabala with the mask of Maa Durga

Nilkantha and the two faces of Bengal are soon joined by another face – a retired schoolteacher from a village in north Bengal. He is a Sanskrit pundit who has internalized the scriptures. Jagannath Bhattacharya represents the Vedic legacy of Bengal. The foursome hit the street in search of a shelter. In Nilkantha’s words “Ei hottomelar deshe kothao nijeke guje debar cheshta” (In this land of mayhem, we look for a crevice to squeeze into). In their meandering journey, Nachiketa keeps passing snide remarks at Bangabala. Their bickering rises to a climactic point in the abode of the ‘Chhau’ guru of Purulia.

After walking for 80 miles the foursome takes a break at the humble abode of the guru who makes gorgeous ‘Chhau’ masks and struggles to keep the artform alive in these troubled times. He laments that city folks come and buy the masks for displaying them in their showcases. The masks are meant to transform mere mortals into gods during a ‘Chhau’ dance recital. Bangabala is all too keen to wear the mask of Durga, but the guru says that the scriptures forbid women from wearing masks. But Bangabala is persistent. Looking deep into her eyes, the guru has an epiphany. He says, “Dance, my girl. Dance. Unless the likes of you start dancing, nothing is going to change.” Bangabala puts on her mask and the scene dissolves to a full blooded ‘Chhau’ dance performance, reminiscent of a documentary Ghatak had made earlier.

Collision between the Vedic ‘mlechchha’ and the indigenous son of the soil

Keno cheye achho go ma mukhopane

In the ‘Chhau’ guru’s eyes, the Brahmin schoolmaster is a ‘mlechchha’, a foreigner to the indigenous land and Sanskrit is a foreign language. The two old men keep bickering over their praise for mother Goddess. The Sanskrit pundit waxes eloquent on the many names of the Mother Goddess in the Sanskrit scriptures. The ‘Chhau’ guru rejects them all in favour of simply ‘Ma’. As the two old men fight over the names of ‘mother’, Bangabala plays with the mask of the Goddess and there comes an abrupt transformation in her personality. She pounces on Nachiketa as he comes back hungry, demanding his meal. She throws the thali full of rice to him and the rice spills on the ground. Nachiketa gets up angrily and walks over the food. Nilkantha breaks into a song, “Keno cheye achho go ma mukhopane” (Why are you looking at me, mother?) – a plaintive address to the motherland by Rabindranath Tagore, where the poet laments that none of her sons bother about the wellbeing of the mother, the motherland. They are all busy minding their own business.

Songs play an important part in giving direction to the seemingly rambling narrative. Early on in the film, “Amaar ange ange ke bajay banshi” (Who plays on rvery part of my body) takes us back to Nilkantha’s youth. We witness a smitten Nilkantha in lustful embrace with Durga.

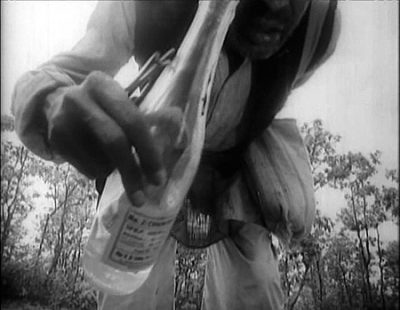

Nilkantha feeds his elixir to the camera

“Namaj amar hoilo na aday” (“My pathway to my union with God is blocked”) sung by a ‘baul like mendicant makes him acutely aware of the changed times. Idealism has given way to corruption. Sacrifice has yielded to compromise. His comrades-in-arm of the past now peddle their creativity in the marketplace. When his erstwhile friend Satyajit Bose offers him scotch whiskey, he refuses. Desi spirits of the indigenous variety are his elixir. At one point he offers a glass to the camera – “I have this elixir to offer you. Do you want some?”

JTG is splattered with many shades of the Bengali language. Nilkantha has his unique choice of Bengali words and phrases, his thoughts occasionally find their expression in English; Bangabala speaks an East Bengali dialect, the school master speaks Sanskrit and the ‘Chhau’ guru speaks the dialect of Purulia. All the shades of Bengali language must have their space in the land called Bengal.

The jotdar who accidentally kills the Sanskrit schoolteacher

But soon, the bearer of an ancient language gets eliminated from the scene. The Sanskrit pundit succumbs to the accidental bullet of ‘jotdar’ Madhav Haldar. The language of the gods has no place in the land of philistines.

At this juncture, the three dancers reappear and perform. The listless spectator looks on. The story continues because the search for shelter is not over.

As the trio walk through a Sal forest, Nilkantha utters “I am a humbug.” Even as he feels shattered by the mayhem around him, he does little to bring about any change. He takes out the bottle to muster courage to knock at the door of Durga’s new home. Durga has taken up the job of a schoolteacher in a village. They hear a passerby singing a familiar song, “Kalo meyer payer tolay dekhechhi tar alor nachon”, reminiscent of Ghatak’s earlier film Ajantrik. The passerby gives directions to the village school. Soon the three homeless arrive at Durga’s door for a second break in their never-ending journey.

In a close-up shot, Nilkantha admits that he is tired. But in the very next long shot, he resolves, “I shall not rest.” Before leaving, he makes a last request to Durga to come to the nearby Sal forest at the crack of dawn with some food and his son Satya. He wants to see Satya’s face in the light of dawn and carry that image in his heart for the rest of his journey. Durga says, “we shall see” and slowly turns her head towards the camera. The fourth wall is momentarily broken, and she makes eye contact with the camera. There is pathos and compassion writ large on her face – as if saying, “I understand this man’s anguish and agony.”

In the Sal Forest, the hiding place of the Naxalite guerilla fighters Nilkantha engages in an argument with the Naxalite leader and admits “I am confused.” Under another Sal tree, Bangabala yawns and dozes off and falls over the shoulder of Nachiketa. She wakes up and dozes off again. Camera keeps cutting from one Sal tree to another – from Nilkantha to Bangabala. The editing hints at the manifestation of dialectical materialism. At this moment the chemistry between Nachiketa and Bangabala suddenly changes from bickering to something like attraction. Both stand up and look at each other with longing. The frame alternates between a long shot and a close up. The soundtrack fills with the sounds of lovemaking, as if whispering the thoughts of the two. The two faces of Bengal at last see eye to eye. The new Bengal, as dreamed by Nilkantha, will synthesise out of the union of thesis and anti-thesis.

This is followed by a police raid and a crossfire where the Naxalites give out a fight but eventually succumb. At dawn, as Nilkantha tries to meet Satya and Durga he is hit by a bullet. A tottering Nilkantha pours the remaining spirit in the bottle onto the camera lens. He has no need for this elixir anymore. But the spectators might need it. Nilkantha falls on the ground and clasps Durga’s hand tight. Over the close up shot of the two hands clasping, we hear the bars of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

The dying Nilkantha utters for the last time “Shob purchhe. Brommando purchhe. Ami purchhi.” Before the last breath escapes him, he compares himself with Madan, the weaver, one of the characters of Manik Bandyopadhyay’s short story ‘Shilpi’. Madan worked on a bare loom because he would not buy thread from a treacherous capitalist. Likewise, Nilkantha had isolated himself from worldly affairs because he refused to sell out to the corrupt world.

The police come and lift his lifeless body. The leader of the police force instructs “Gently.” A procession of the police, Bangabala, Nachiketa, Durga and Satya winds down the rugged rocky terrain. Ululation and beating of cymbals begin on the soundtrack. Camera faces Durga. She covers her head as if she is about to enter a place of worship.

Three dancers appear again. They dance to the tune of joyous music. The haggard man slowly looks up into the camera – as if finally aroused. The ‘dorma’ of the title sequence reappears. Now it bears a swastika like sign. It is a sign of good omen.

Ritwik Ghatak died two years after completing Jukti Takka Arr Gappo. He was an incorrigible optimist. All his films, despite narrating tales of loss, separation, sacrifice and denial, end on a note of hope, promising resurgence. His last film is no exception.

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.