& Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel  & Telegram

& Telegram  Channel

Channel

The Calcutta Film Society was registered in October 1947, with Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Dasgupta, Manojendu Majumdar and Purnendu Narayan as the founding members. The society became an important and integral part of the film culture that thrived in Calcutta and remained relevant for decades even though most of its founding members are no more. A Silhouette retrospective.

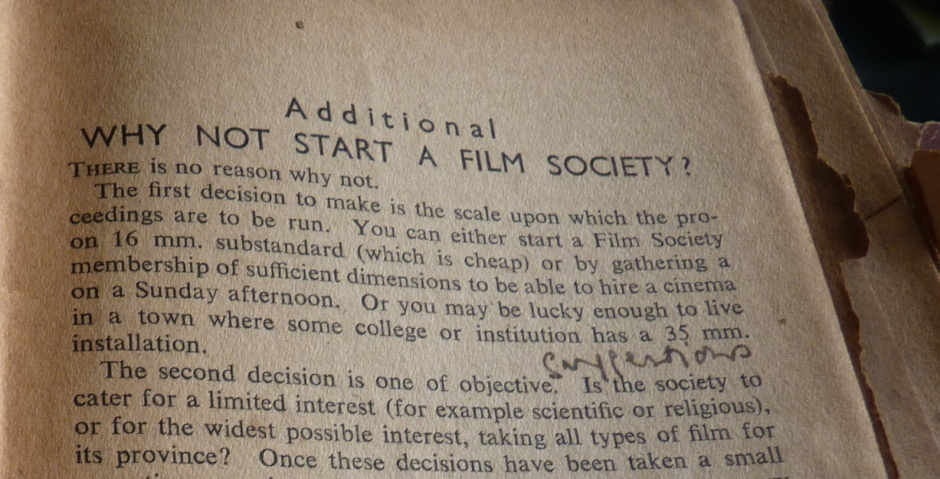

“Why not start a Film Society?” – Excerpt from Film by Roger Manvell (Pic Courtesy: Author)

“WHY NOT START A FILM SOCIETY?

There is no reason why not.

The first decision to make is the scale upon which the proceedings are to be run. You can either start a film society on 16 mm substandard which is cheap or by gathering a membership of sufficient dimensions to be able to hire a cinema on a Sunday afternoon. Or you may be lucky enough to live in a town where some college or institution has a 35 mm installation.” – an excerpt from the last chapter of a book called Film by Roger Manvell, a Pelican Paperback published in 1946.

In 1946, serious studies on cinema were on firm footing as individual and group efforts, more than institutionalized efforts. The British Film Institute had been founded in 1933 with the mission to promote access to and appreciation for the widest range of world cinema; around the same year, Rudolph Arnheim, a believer in the Gestalt Theory, had published his book Film as Art and cinema was unquestionably accepted as an art form, to be taken seriously, analysed and written about. However, in spite of the first film theories being propounded by Hugo Munsterberg, a professor of psychology at Harvard and by a poet Vachel Lindsay, Film Studies had not yet emerged as an academic discipline to be pursued in the universities. To study the craft of film making, there were only two film schools – the VGIK in Moscow, established in 1919 and the USC (University of Southern California) School of Cinematic Arts established in 1929. The task of disseminating the refined practice of film appreciation was left to film societies. Hence Roger Manvell’s appeal to his readers, “Why not start a film society?”

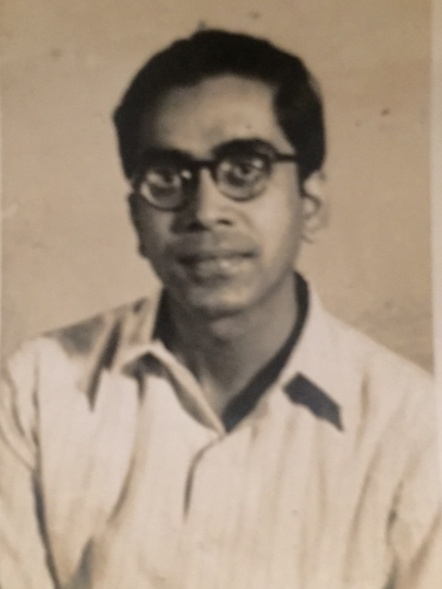

Chidananda Dasgupta – CFS Founder member and first joint secretary (Pic Courtesy: Author)

In Calcutta, the erstwhile capital of British India, a young man named Purnendu Narayan, a junior officer in the Steel Authority of India, procured a copy of Roger Manvell’s Film and underlined the lines, “A well organized Film Society is one of the greatest pleasures obtainable, and a definite addition to the social life of any community.” He showed the book to his cousin Supriya’s husband Chidananda Das Gupta and to his close friend Manojendu Majumdar, who was then a junior officer in the Deptt. Of Commercial Intelligence & Statistics. Chidananda, the son of a Brahmo Acharya, knew Satyajit Ray through his Brahmo connection. He forwarded the proposal of starting a film society to Satyajit because he was aware of his friend’s cinephilia. Satyajit Ray has written in Our Films Their Films that he used to go to movies with a note book and took notes of points, first about acting and mise–en–scene and then about direction. The idea of starting a film society appealed to Ray in 1947.

India had become independent just a few months back and optimism was in the air. The four young men decided to take the plunge. Calcutta Film Society was registered in October 1947, with Satyajit Ray and Chidananda Dasgupta as joint secretaries, Manojendu Majumdar as treasurer and Purnendu Narayan as librarian. At the time of the society’s formation, Satyajit Ray was the chief visualizer at the advertising agency DJ Keymer and Chidananda Dasgupta was an accounts executive in the same company.

Satyajit Ray – CFS Founder member and first joint secretary (Pic Courtesy: Internet)

The activities of the society were inaugurated with the screening of the film The Great Waltz in Satyajit Ray’s maternal uncle’s home near Triangular Park off Rashbehari Avenue. A 16 mm projector had been hired for the purpose. Besides the four founder members and Ray’s extended family, a handful of common friends had dropped in for the screening.

The Calcutta Film Society (CFS) was not the first film society to have been set up in India. The Bombay Film Society preceded it by a year or so. But the formative years of CFS are replete with curious stories that throw some light on the life and times in a city caught in the cross currents of a social change. The four young members decided to use poet Jibanananda Das’s drawing room for the weekly meetings, within the understanding that they would pay a small monthly amount to the poet to help him out of his dire financial situation. However, after a few weeks, the landlord raised objections, saying that the film people were vitiating the environment of his house. The foursome had a difficult time in convincing the landlord that they had nothing to do with the big bad world of ‘cinema’. Eventually they were allowed to continue when the landlord was assured that no film star would ever be invited to his house.

Manojendu Majumdar – CFS Founder member and first treasurer(Pic Courtesy: Author)

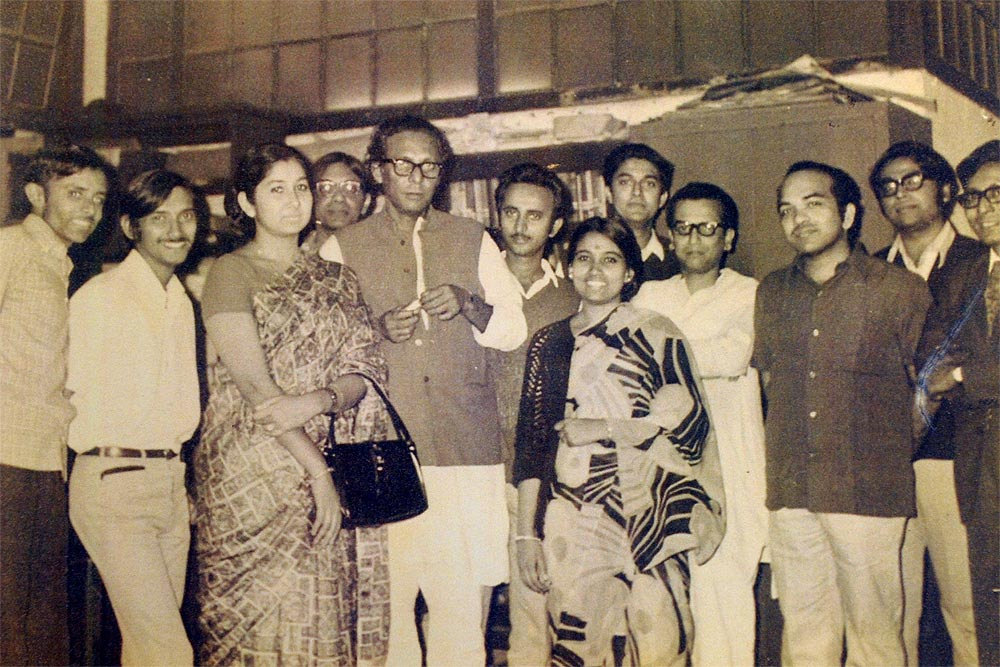

The weekly discussions of the film society members were many times pivoted around articles in the film journal Sight and Sound. An article that had come out in Sight and Sound was called ‘The Kid – Eisenstein’s evaluation of Charlie Chaplin’. This article later inspired Mrinal Sen to write a book on Chaplin in Bengali. Sen’s book Charlie Chaplin, was published by New Age Publishers in 1953. Mrinal Sen used to be a frequent visitor to the Calcutta Film Society sessions.

Just as creative minds like Banshi Chandra Gupta, Madhav De (Bishnu De’s brother), Radha Prasad Gupta became members of Calcutta Film Society, so did many British who had stayed on in India as heads of companies like Metal Box, Shaw Wallace, Imperial Tobacco Company and Dunlop Tyres. The films were procured from the British Council and American Information Centre. Initially the screening venue continued to be Ray’s maternal uncle’s house, ‘The Home of the Das-es’ near Triangular Park. 16 mm print of the British documentary Night Mail was screened and discussed. Interestingly, Roger Manvell himself was a great admirer of John Griersson, the father of the documentary movement in Britain, a movement that had shown the world how drab realities could be turned into visual poetry. Night Mail, a film about the British Post and Telegraph system, is a poetic exposition of the punctuality and efficiency of the system, narrated entirely from the point of view of the ‘workers’ who took the young joiners under their wings and instilled in them the sense of responsibility and pride. The rhythmic editing pattern in the last sequence of Night Mail, where the shots are cut to the rhythm of W.H Auden’s poem and the rhythmic movement of the mail train, were discussed and admired and screened again at the Calcutta Film Society screening.

Purnendu Narayan – CFS Founder member and first librarian (Pic Courtesy: Author)

Gradually, as the society membership grew, screenings were held at public spaces like The National Library or Artistry House or sometimes in school halls. Some of these screening venues were given free to the young members, sometimes they had to be hired for a small fee. Not all screenings ended amicably. Once, for example, Chidananda Dasgupta had invited some of his American friends to the screening of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a 1939 Hollywood political comedy starring James Stewart. The Americans were furious, saying that CFS was out to do anti American propaganda. Dasgupta had a tough time explaining to them that the film was actually a celebration of the triumph of the ordinary American, a reassurance to millions of Americans that they have a say in the system that governs them.

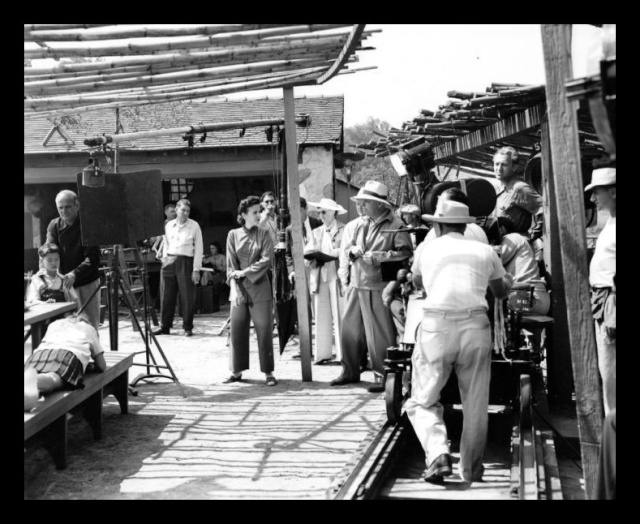

Jean Renoir came over to India for shooting the film River. First he came on a reconnaissance visit and then he came with his entire shooting unit. Satyajit Ray and the other members of Calcutta Film Society followed him like a shadow. He was given a public reception at Artistry House. One member of Calcutta Film Society stood up and asked him, “Monsieur Renoir, what goes wrong with competent continental directors when they go to Hollywood?” Renoir’s producer was also there in the gathering. So he gulped a few words and said, “In Europe we are used to working with simple equipment and a modest budget. When we go to America, we are overwhelmed by the excess of all kinds of resources.”

Besides Artistry Hall, Sunday morning screenings were held at the Deepti Cinema in Tollygunj. Manojendu Majumdar vividly remembers two films – a Mexican film Portrait of Maria and a Marathi film Ram Shastri. Important guests were specially invited for these screenings. Among those who came, were Claude Journot, the cultural counselor of the French consulate and the Director of Alliance Francaise Christine Bossenec.

French director Jean Renoir shooting River in Calcutta (Pic Courtesy: Internet)

In spite of its humble beginnings and near zero budget activities, the Calcutta Film Society attracted every serious cinephile in town. Hari Sadhan Dasgupta became a member of CFS on his return from USA after completing the course on film craft. He took on the task of turning Tagore’s novel Ghare Baire into a film and took Satyajit Ray as his associate. Unfortunately, the project did not progress beyond the scripting stage.

Around this time, Satyajit Ray was sent to England by DJ Keymer for training in the latest technology in the visual arts. Ray, accompanied by his wife, was there for six months. This is the time he watched Bicycle Thieves several times and witnessed Mozart’s opera Magic Flute performed live on stage. Ray also visited the office of the British Film Institute and told them about Calcutta Film Society. BFI was impressed. They provided Battleship Potemkin to Satyajit Ray on permanent loan. But when Ray came back with the film cans, the customs office in Calcutta imposed a tax of Rs. 400/- on the cans. The customs inspector could not be convinced that the film was meant for educational purpose. He had not heard of the film and he did not understand how a film could serve any educational purpose. Satyajit Ray wrote to BFI with a request for a certificate about the film. But those were the days of super snail mails. Ray got impatient and paid the fine to release the cans from the customs office.

Incidentally, Battleship Potemkin had been banned in many parts of the world, including England and India, during the British rule. It was feared that the film would incite revolutionary action among the masses and so ruling authorities were skeptical about releasing this film for public viewing. This would be the Indians’ first chance to watch the classic. Roger Manvell had waxed eloquent about this film in his book and John Grierson had been heavily infuenced by it. In his maiden film Drifters, Griersson had followed Eisenstein’s style of ‘collision montage’.

Mrinal Sen with CFS members at Calcutta 71 inaugural show (Pic Courtesy: Internet)

Incidentally, the London Film Society, formed in 1925, was a pioneer in the cine club movement. Films ignored or forbidden by the commercial circuit were screened here. One such film, banned by the British Censor Board, was The Battleship Potemkin. The film was premiered in London by the London Film Society.

Battleship Potemkin was screened at Artistry House and subsequently at other venues too. After watching the film at Artistry House, Tore Hackanson, a high ranking British officer at an English merchant house commented, “I feel like kicking anyone in uniform.” The Calcuttan’s romance with Battleship Potemkin ended when the film cans mysteriously disappeared from the dickey of Satyajit Ray’s car.

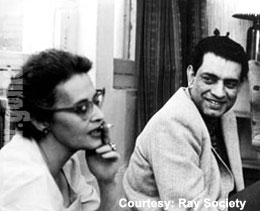

Marie Seton with Satyajit Ray (Pic Courtesy: Internet)

Friends of Soviet Union, located on 46 Dharamtala Street, became a friend of Calcutta Film Society too. Their office became not only a venue for holding discussion sessions on films, but they lent films like October, Ten Days that Shook the World, Alexander Nevsky, Ivan the Terrible and Dovzhenko’s Road to Life to the Society for screening. Perhaps this generous gesture was an extension of the foreign policy that Nehru was forging ahead. Be that as it may, the film lovers of Calcutta got an exceptional exposure to Russian classics thanks to the generosity of Friends of the Soviet Union.

To get a taste of the classics from other countries, such as Rashomon from Japan, the Indian audience had to wait till the first international film festival held in 1952. The same year Calcutta Film Society became moribund. Satyajit Ray had begun his long journey on the little road, trying to put together funds for his first film Pather Panchali. Chidananda Dasgupta had taken up a high profile job with the ITC and the other two founder members got busy with their family responsibilities.

Calcutta Film Society was revived in 1956 by Marie Seton, a film scholar from the British Film Institute. Having just completed a tome on Eisenstein, Seton came to Calcutta and got acquainted with Satyajit Ray. Ray’s Pather Panchali had just received the Best Human Document award at Cannes. Marie Seton not only revived Calcutta Film Society with her lively discussions on cinema, she also wrote Portrait of a Director, a biography of the founder secretary of Calcutta Film Society, the man who brought India to the map of world cinema.

The Calcutta Film Society in early 2016 (Pic Courtesy: Internet)

After Calcutta Film Society, several other film societies came up in India. In 1959, the Federation of Film Societies of India was formed, with its registered office in Kolkata. Six existing film societies in the country, namely Calcutta Film Society, Delhi Film Society, Madras Film Society, Patna Film Society, Bombay Film Society and Roorkee Film Society were the first members of Federation of Film Societies. The first Executive Committee of this Federation comprised Satyajit Ray as President, three Vice-Presidents, namely Ms Ammu Swaminathan (Madras), Robert Hawkins (Bombay), S.Gopalan (Delhi), two Joint Secretaries, Ms Vijaya Mulay (Delhi) and Chidananda Dasgupta (Calcutta), D Pramanik and Abul Hasan as Joint Treasurers, and members R Anantharaman, K L Khandpur, Jag Mohan, A Rehman, A Roychowdhury and Ms. Rita Ray.

Today, Calcutta Film Society has become moribund once again. There had been some attempts to revive the Society, but easy availability of films has made film societies redundant. According to a recent article by Dola Mitra in Outlook, CFS has not been able to pay its rent for the office room in LIC building and they are facing eviction in the near future. The eviction is the last nail in the coffin of a movement once spearheaded by India’s most celebrated filmmaker.

More to read

Remembering PK Nair – ‘He Changed the Way We Viewed Cinema’

60 Years of Pather Panchali and Some Questions on Indian Cinema

Whether you are new or veteran, you are important. Please contribute with your articles on cinema, we are looking forward for an association. Send your writings to amitava@silhouette-magazine.com

We are editorially independent, not funded, supported or influenced by investors or agencies. We try to keep our content easily readable in an undisturbed interface, not swamped by advertisements and pop-ups. Our mission is to provide a platform you can call your own creative outlet and everyone from renowned authors and critics to budding bloggers, artists, teen writers and kids love to build their own space here and share with the world.

When readers like you contribute, big or small, it goes directly into funding our initiative. Your support helps us to keep striving towards making our content better. And yes, we need to build on this year after year. Support LnC-Silhouette with a little amount – and it only takes a minute. Thank you

Silhouette Magazine publishes articles, reviews, critiques and interviews and other cinema-related works, artworks, photographs and other publishable material contributed by writers and critics as a friendly gesture. The opinions shared by the writers and critics are their personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of Silhouette Magazine. Images on Silhouette Magazine are posted for the sole purpose of academic interest and to illuminate the text. The images and screen shots are the copyright of their original owners. Silhouette Magazine strives to provide attribution wherever possible. Images used in the posts have been procured from the contributors themselves, public forums, social networking sites, publicity releases, YouTube, Pixabay and Creative Commons. Please inform us if any of the images used here are copyrighted, we will pull those images down.